Mask-ulinity and Feminicide: Argentine Collective Activism During Covid-19

By Madison Felman-Panagotacos

During the ongoing pandemic, we in the United States have been reckoning with a population that refuses to don masks, an overwhelmingly male section of the population.[1] In May, writer, historian, and activist Rebecca Solnit responded to this phenomenon by deeming the “maskless men of the pandemic” actors of a “masculinity as radical selfishness… [that has] taken a huge toll by insisting that we don’t have to respond to the pandemic because the ‘we’ that is not responding imagines itself as invulnerable and full of unlimited arm-swinging rights.”[2] Women and non-binary people have been left to protect themselves and serve as caretakers to those infected. In Argentina, this misguided expression of masculinity (and the response to it) takes a different and more immediately lethal form.

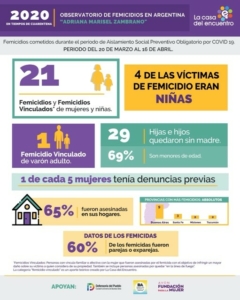

During quarantine, rates of intrafamilial violence and feminicide[3] in Argentina have risen drastically. Just on the first day of mandatory quarantine, there were 41 police reports of intrafamilial violence in Buenos Aires. According to the news site Unidiversidad, “desde que se decretó el aislamiento social preventivo y obligatorio a raíz de la pandemia por coronavirus COVID-19 las denuncias por violencia de género han aumentado alrededor de un 39%”[4] [since preventative and obligatory social isolation was decreed as a result of the coronavirus COVID-19, reports of gender-based violence have increased by about 39%].[5] The state of Argentina does not maintain or publish records of feminicide. However, since 2003, el Observatorio de Femicidios Adriana Marisel Zambrano de la Casa del Encuentro [the Meeting House’s Adriana Marisel Zambrano Feminicide Observatory] has issued an annual report of statistics on assassinated women. Instead of waiting until the end of 2020 to publish information about those who were assassinated during this time of COVID, el Observatorio issued an overview of feminicides committed during the first month of mandatory preventative social distancing. Between March 20 and April 16, 2020, el Observatorio documented 21 “femicidios vinculados” [linked feminicides]. This terminology indicates feminicide committed by someone with a familial link to the victim. One out of five feminicide victims had previously formally reported their attacker. Of the victims, 60 percent were assassinated by partners or ex-partners, and 65 percent were killed in their own homes.

To fully understand the impact of these statistics, it is important to know the legacy of gendered violence and mobilizations against it in Argentina. Historically, women have been relegated to the domestic sphere, taking care of their husbands and children. Women, as wives and mothers, were expected to be subordinate to their husbands and stay within their perceived sphere of influence—the home. The 1869 Civil Code established reciprocal, but hierarchical, rights for men and women, with a woman having the right to her husband’s financial support, but also requiring her husband’s permission to be present in the public sphere. In La guerra contra las mujeres [The War on Women], anthropologist Rita Segato describes the emergence of women from the private into the public sphere as an infringement upon the masculine domain, including the legal and political systems that define citizenship. Argentine women did not gain the right to suffrage until 1947. In 1987, President Raúl Alfonsín legalized divorce, which also legally established gender equality between husband and wife.

However, there were (and are) not sufficient legal protections in place to truly enforce this gender equality, especially with regards to intimate partner violence. Until the late 20th century, a husband who committed violence against his wife was not considered criminal, but rather, viewed as exercising patriarchal authority over his property.[6] Governments worldwide did not begin to move toward legally restricting such actions on a broad scale until the 1990s. The first federal law to do so in Argentina was passed in 2009—the Ley de protección integral para prevenir, sancionar y erradicar la violencia contra las mujeres en los ámbitos en que desarrollen sus relaciones interpersonales [Comprehensive Protection Act to Prevent, Punish, and Eradicate Violence Against Women in the Areas Where They Develop Their Interpersonal Relationships] (Law 26.485).[7] By specifying in its title that the law was in place to combat violence in interpersonal relationships, Law 26.485 made public the formerly private issue of gendered violence. Despite this and subsequent laws passed to target feminicide, Human Rights Watch reported there were 254 feminicides in Argentina in 2016, but only 22 convictions.[8] Gender violence had been made a criminal offense, but the law has lacked sufficient enforcement.

Like other movements for human rights in Argentina, the fight against gender violence has gained the most traction through public manifestations, which highlights the lack of action on the part of the state. The collective NiUnaMenos, a group formed in 2015 and united in the fight against machista violence [violence motivated by a culture of masculine pride], is the most notorious contemporary actor. In their Carta Orgánica, a collectively written letter that puts forth the group’s goals and practices, NiUnaMenos notes that they move into the streets as political subjects. Furthermore, they prioritize an “amistad política” [political friendship] predicated on collective trust and mutual aid.[9] NiUnaMenos has experienced much of its success from occupying the public squares Plaza de Mayo and Plaza del Congreso in Buenos Aires, and their equivalents in other cities. But their members don’t do so as individual activists, they do so as a collective. This collectivity, not just in action but also in shared knowledge—information circulated for the masses via social media—is what fuels the movement and its successes. Perhaps the most important aspect of this collectivity is solidarity, existing in unity and fellowship with others, bound by shared objectives and experiences.

Since Argentina enacted mandatory social distancing, the Plaza de Mayo has remained vacant, without even the Thursday rondas from the Madres de Plaza de Mayo for the first time in decades.[10] Public activists have been forced back into the private sphere by the menace of a pandemic. How are we supposed to gather in protest during quarantine and social distancing? Social media strategies allow groups like NiUnaMenos to disseminate information and organize collective action at a distance. Feminist social media attempt to counteract the isolation and violence of quarantine by returning the discourse of gendered violence to the public sphere and generating narratives of solidarity and mutual aid.

One of the first widely publicized feminicides under quarantine was that of Camila Tarocco, a 26-year-old woman from the Province of Buenos Aires whose body was found on April 16, 2020, eleven days after her disappearance. Her friend Haydeé, the last person to see her, reported that Camila had plans to leave her partner Ariel, whom she lived with along with their children. Haydeé had been present when Camila told Ariel that she planned to move, and he calmly received the information. However, in private, Camila confessed that she feared both Ariel and the police. Haydeé told the newspaper La Nación [the Nation], “Estaba la policía realizando rondas por la vigilancia de la cuarentena y ella tenía miedo de ir hasta su casa porque pensó que la policía podía decirle algo” [The police were conducting quarantine surveillance rounds and she was afraid to go home because she thought the police could say something to her].[11] Camila did not just fear the man she was fleeing, but also the police that would enforce social distancing restrictions more stringently than protections for women fearing intimate partner violence.

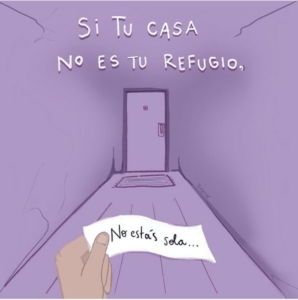

Instagram post from Ni Una Menos (@_niunamenos_), shared on April 22, 2020. “If your house isn’t your shelter, you’re not alone…”

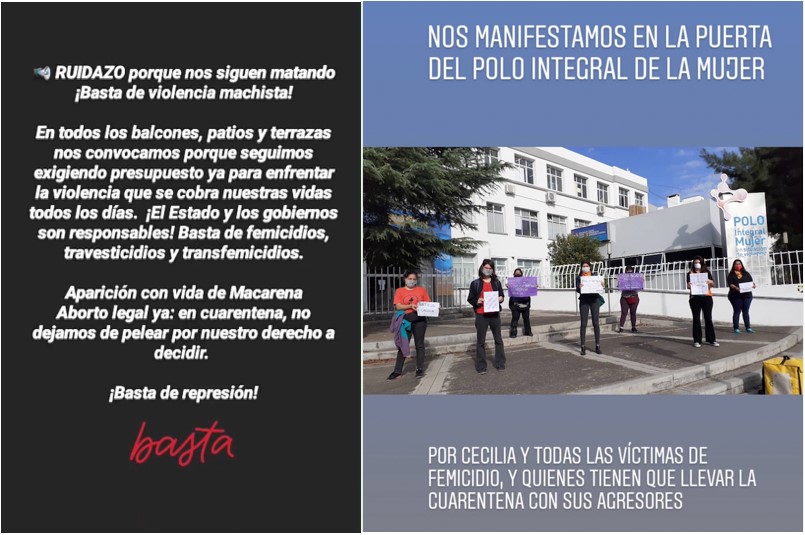

Feminist collectives publicize information and resources for those who need to leave their homes to escape domestic or gendered violence on their social media accounts. On April 22, 2020, the Instagram account of NiUnaMenos shared this image: “Si tu casa no es tu refugio, no estás sola…” [If your house isn’t your shelter, you’re not alone…”[12] The caption contained information on steps to take when leaving the home to seek help. For those who cannot go out and are in immediate danger, they suggested using one’s voice as a means of defense and leaving windows open, if possible, so that others can hear. NiUnaMenos and other collectives have also used social media to organize auditory protests called ruidazos, meaning “loud noises.” Ruidazos are instances of people making loud noises in unison as a form of socially distanced protest. NiUnaMenos Cordoba organized a ruidazo, publicized on Instagram, in protest of machista violence, feminicide, and restriction of abortion rights. In their post, they urge members of the community to join together on all the balconies, patios, and terraces of Cordoba—a quarantine-compliant form of protest against the invisibilization of gender violence.

Instagram story from Colectivo Ni Una Menos Córdoba (@niunamenoscba) publicizing a ruidazo, shared May 12, 2020. “RUIDAZO because they keep killing us. Enough with machista violence! On all the balconies, patios, and terraces, we convene because we continue to call for a budget to confront the violence that continues claiming out lives every day. The State and the governments are responsible! Enough with femicides, travesticides, and trans-femicides. We want Macarena alive [and] legal abortion: in quarantine, we won’t stop fighting for our right to decide. Enough repression! Enough.” The image depicts a protest at the Polo Intgral de la Mujer. “We are protesting at the gate of the Polo Integral de la Mujer. For Celia and all victims of feminicide, and those who have to spend quarantine with their aggressors.”

Instagram story from Asamblea Ni Una Menos Córdoba (@niunamenoscba) providing information about a protest at the Polo de la Mujer, shared May 14, 2020 and since removed. “We are protesting in front of the Polo de la Mujer, peacefully and following health guidelines and physical distancing. We find ourselves faced with intimidation from the Córdoba Police, who grow in quantity minute to minute. Our fights are not in quarantine, protesting against machista violence is also essential. We invite you to share and pronounce it.”

These posts also highlight the double standard behind the form of policing that Camila feared—the strict regulation of quarantine restrictions, but the loose enforcement of laws prohibiting intimate partner violence. The group that gathered outside of the Polo de la Mujer [Women’s Hub], a state-funded site to help women who experience violence, in Cordoba on May 14 shared their experiences of intimidation at the hands of the police, including officers taking photos of the protesters without permission. This strict policing of quarantine rules acknowledges the mortal risk of COVID-19, but not of what Segato terms “feminogenocidio” [feminogenocide]. Segato’s terminology moves beyond feminicide—the killing of women for being women—to their mass killing with impunity.

Social media pages of activist collectives have strongly denounced feminicides as a pandemic analogue to COVID-19, made worse by the surge in violence during social distancing. The Agrupación Periodistas Argentinas [Association of Argentine Women Journalists], a collective of women journalists, took a stand together by photographing themselves individually with masks and face-coverings bearing the slogan NiUnaMenos. Along with these images, they released the statement,

Hoy, impulsamos esta campaña para hacer visible la pandemia de femicidios y travesticidios y exigimos presupuesto y medidas concretas para combatirlo y prevenirlo. También para que la búsqueda de mujeres y travestis desapareciera como una prioridad… Sabemos que la información es una herramienta clave y por eso el Estado debe cumplir con la obligación de llevar un registro diario de feminicidios, travesticidios y denuncias de violencia. Es urgente y es ahora una oportunidad para que salde esa deuda histórica que expresa el grito Ni Una Menos.[13]

[Today, we are promoting this campaign to make visible the pandemic of feminicides and trans murders and to demand a budget and concrete measures to combat it and to prevent it. Also, to make the search for disappeared women and trans people a priority… We know that this information is a key tool and that’s why the State must comply with its obligation to keep a daily record of feminicides, trans murders, and reports of violence. It is urgent and it is now an opportunity to pay of this historical debt expressed by the cry Ni Una Menos.]

Their statement not only discusses feminicide as its own pandemic, but also implores the state to act by recording the data of these crimes.

The most important aspect of these social media publications is the establishment of a digital collective. Notably, the Agrupación did not publish the images of women individually. Rather, they shared a collage of faces side-by-side. In other Twitter publications, they shared images of two or more women at a time. By publishing their individual photos together, the Agrupación was able to establish a digital collective front.

Compilation of photographs of journalists wearing masks with Ni Una Menos written on them. Shared by the Agrupación Periodistas Argentinas via Twitter on April 17, 2020 (@PeriodistasArg).

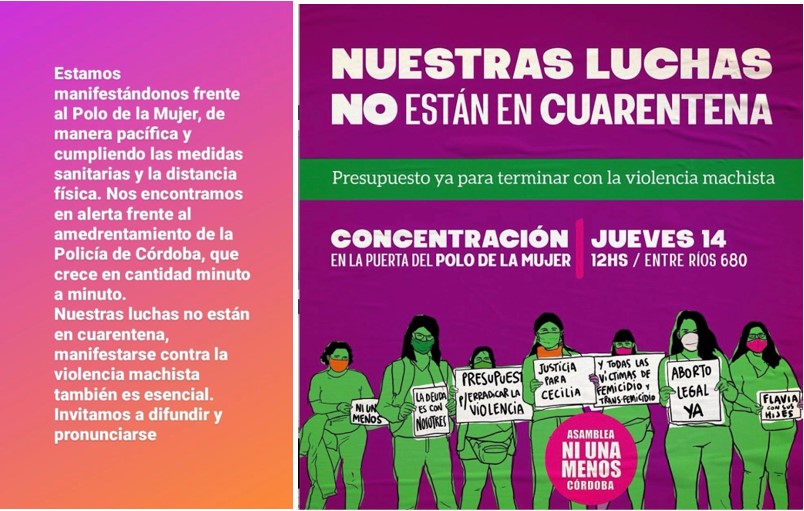

The same is true of the advertisements stating “Nuestras luchas no están en cuarentena” [Our struggles aren’t in quarantine]. It depicts a group of women standing together and fighting for nuestras luchas. A key aspect of the movements from NiUnaMenos, the Agrupación, and countless other feminist groups in Argentina has been the collectivity celebrated in NiUnaMenos’s Carta orgánica. Without solidarity, the isolation produced by protective measures against COVID-19 relegates women back to the domestic sphere on their own. By letting potential victims of gendered violence know that they are not alone, feminist social media pages are encouraging a digital collective, parallel to collectives that form organically in person.

Madison Felman-Panagotacos is a doctoral candidate in Hispanic Languages and Literatures at UCLA and a Fulbright-Hays scholar. Her research centers on non-patriarchal parenthood, abortion rights, and representations of women’s corpses. You can find her work in the LA Review of Books, A contracorriente, and Imagofagia. Felman-Panagotacos is the recipient of a 2020 CSW Spring Travel Grant.

[1] Emily Willingham, “The Condoms of the Face: Why Some Men Refuse to Wear Masks,” Scientific American, June 29, 2020, accessed December 4, 2020,

Fernando Duarte, “Coronavirus face masks: Why men are less likely to wear masks,” BBC World Service, July 18, 2020, accessed December 4, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-53446827.

[2] Rebecca Solnit, “Masculinity As Radical Selfishness: Rebecca Solnit on the Maskless Men of the Pandemic,” LitHub, May 29, 2020, accessed May 30, 2020,

[3] I use the term feminicide instead of the more common femicide following the logic of Rosa-Linda Fregoso and Cynthia Bejarano in their introduction to Terrorizing Women: Feminicide in the Americas (2010): “In arguing for the use of the term feminicide over femicide, we draw from a feminist analytical perspective that interrupts essentialist notions of female identity that equate gender and biological sex and looks instead to the gendered nature of practices and behaviors, along with the performance of gender norms” (3).

[4] Observatorio de Femicidios Adriana Marisel Zambrano, “Hubo 21 víctimas de femicidio desde que se decretó la cuarentena,” Unidiversidad, April 16, 2020, accessed April 29, 2020, http://www.unidiversidad.com.ar/hubo-21-victimas-de-femicidio-desde-que-se-decreto-la-cuarentena.

[5] All translations are by the author.

[6] Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos, “Protección Contra la Violencia Familiar,” accessed April 30, 2020, http://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/90000-94999/93554/norma.htm.

[7] Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos, “Ley de Protección Integral a las Mujeres,” accessed April 30, 2020, http://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/150000-154999/152155/norma.htm.

[8] “Argentina: Events of 2017,” Human Rights Watch, accessed May 12, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2018/country-chapters/argentina#.

[9] NiUnaMenos, “Carta Orgánica,” June 3, 2017, accessed April 29, 2020,

http://niunamenos.org.ar/quienes-somos/carta-organica/.

[10] The Madres de Plaza de Mayo [Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo] have held weekly “rondas” [rounds] in the main square in front of the presidential building since 1978 in protest of the disappearances under the 1976-1983 military dictatorship.

[11] “Femicidio en Moreno: horas antes de que la maten le aviso a una amiga que se iba a mudar por temor,” La Nación, April 15, 2020, accessed April 29, 2020,

https://www.lanacion.com.ar/seguridad/horas-antes-asesinen-le-aviso-amiga-se-nid2354564.

[12] NiUnaMenos (@_niunamenos_), “Si tu casa no es tu refugio, no estás sola…,” Instagram photo, April 22, 2020, https://www.instagram.com/p/B_SwE5QgW2h/?igshid=1gi05ypz2r1y3.

[13] Paulina Maldonado, “Campaña contra la pandemia de femicidios,” Perfil, April 17, 2020, accessed April 30, 2020,