Domestic Workers: The Original Gig Workers

By Magally Miranda

The UCLA Center for the Study of Women will honor Ai-jen Poo, Director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, (NDWA) with the 2019 Distinguished Leader in Feminism Award on May 30, 2019. Below, CSW Travel Grant Recipient Magally Miranda writes about recent campaigns by the NDWA. To meet Ai-jen Poo and hear about this work in person, join us at our Awards and Benefit Reception on May 30!

In 2017, Google awarded four nonprofits and private businesses with grant money as part of an initiative to address issues emerging from the changing nature of work: “the rise of the gig economy, new technological advances, [and] demographic changes.” One of the organizations that was awarded a several million dollar grant was the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA), an NGO that represents 2.5 million domestic workers in the United States. The NDWA has been developing an app called Alia (the name is derived from the word aliada meaning ally in Spanish) that would help domestic workers accrue funds from their employers that they can then use to access benefits like paid sick time and health insurance; the NDWA say domestic workers are “the original gig workers.”

One major issue emerging from the changing nature of work has been called “the benefits problem,” where flexible independent contractors are ineligible for benefits like paid time off or sick leave. With the personal services industry and the gig economy projected to grow in the coming years, the changing nature of work is disrupting work as we know it. A recent report on ride-hailing in Los Angeles by the UCLA Labor Center found that 4 out of 5 drivers wanted access to workers’ compensation and health insurance, benefits that they lack despite many of them working full time. On a more morose note, the aftermath of the tragic death of Pablo Avendano while working for the food delivery platform Caviar illustrates the impacts of a lack of any corporate responsibility for the well-being of independent contractors. Many companies like Caviar do not take responsibility for workers by arguing that they are merely a platform to connect clients and independent contractors who are not their employees and thus not their responsibility.

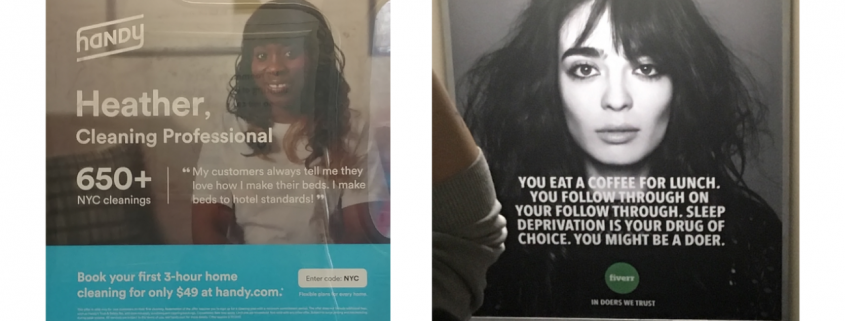

Just as the Fight for 15 campaign changed the image of the average fast food worker, so too are domestic workers trying to change the face of the gig economy. In the Fight for 15 movement, a propaganda campaign was launched to de-infantilize the fast food worker image. Fast food workers had been depicted in media and the popular imagination as high school students for whom working at a fast food chain was a first job. Because of this image, there had been a popular perception that it would be excessive to make the minimum wage in the industry $15/hr. The campaign showed the real face of fast food workers, many of whom were heads of households, working full time and for whom a fast food job was the main source of income. They also challenged elitist stereotypes of uneducated “burger flippers” and fought for the recognition of fast food work as dignified.

The gig economy suffers from its own representation problem, in the opposite direction. Unlike the stereotype of the typical fast food worker as young and uneducated, the gig worker is perceived in popular culture as a young, middle class and often white creative for whom “gigs” are a means for supplemental income. While some people do approach the gig economy as a form of temporary or supplemental income, new findings are changing that perception. For instance, the same UCLA Labor Center report of ride-hailing in Los Angeles found that two out of three drivers drove as their main source of income and for one out of two drivers, this gig was their only job.

Domestic workers are pigeonholed in a similar way by specifically gendered and racialized tropes, like what I call the Kelly girl effect and the chacha effect. In the 1940s, entrepreneur William Russell Kelly founded the modern temporary staffing industry. Temporary workers were known as “Kelly girls,” a title that connoted a worker who was female, young and treated as flexible labor, not as a full employee. The Kelly girl was not the head of household or breadwinner, but rather a pleasantly middle-class woman earning extra income or working as a hobby to kill time while her husband was at work. Her income is supplemental at best or otherwise altogether superfluous to her family. Her labor is flexible. She can be hired and fired at the will of her employer. And she is not entitled to benefits like health care or paid time off. Similar to the Kelly girl effect, the ‘chacha effect describes a worker who is devalued by her gender, but also by her Latinidad, often times of indigenous descent. The phrase ‘chacha is short for muchacha, or girl, in Spanish. Often portrayed in Latinx telenovelas as a rural indigenous woman who moved to the city to work for a mestizo family, I use the phrase here also to refer to Latina women who move from rural or urban cities in Latin America to work in cities in the United States. Infantilization is at play with the ‘chacha effect, as the worker is perceived to be young, robust and rewarded with work experience and personal referrals to make up for what they are not paid in adequate wages or benefits. Both of these gendered and racialized tropes feed into the logics of the modern gig economy.

The new portable benefits application from the National Domestic Workers Alliance Fair Care Labs, Alia, is helping to ameliorate these issues in the gig economy and to undermine the devaluation of domestic work. Alia is using technology to make it easier for than ever for people who hire domestic workers to do the right thing. Many people want to do the right thing and take care of the people who take care of their homes and their loved ones but they simply do not know how. Alia is using the sharing economy to make it simple for employers to become allies to domestic workers. Employers can now simply visit myalia.org, find a cleaner using their phone number or email address and pledge a small contribution ($5 per cleaning suggested). In the matter of minutes, clients can make a one-time contribution or set up a recurring payment plan and workers can pool their contributions to access benefits like paid sick leave and health care. Alia developers are hoping to sign up tens of thousands of users across the country.

Alia is a good example of how social movements in real life are creating spaces of allyship on the net. In 2010, the NDWA launched a program called Hand in Hand. This network of domestic workers and employers was forged in the trenches of the struggle to pass Domestic Workers Bill of Rights legislation in New York City. When the legislation passed, organizers reflected on the fact that a huge asset was the allyship of Jewish employers who had testified for domestic workers throughout the campaign. Hand in Hand has become a full-fledged NGO today. According to Hand in Hand’s website, they are working to help “employers recognize that their homes are workplaces—and that we have both legal obligations and opportunities to make our homes workplaces that they can be proud of.” They argue that many clients are themselves subjects who should not have to shoulder the burden of paying for care work alone–working women, seniors and people with disabilities–but that by joining domestic workers they can push for structural changes in the system to make it accessible. They say that Hand in Hand members join because they want a sense of community and to be part of a movement with shared values. Hand in Hand held workshops throughout the country where organizers would ask employees, many of whom were themselves working women, if they wouldn’t want paid sick leave when they fell ill. When they overwhelmingly responded “yes, of course” the workshop leaders would respond with, “well we think domestic workers should have that right too?” In this way, organizers elevated a sense of shared values about the value of women’s work and anti-racism and an affirmation of the dignity of domestic workers. Alia is taking the ethics of these workshops online. As Kira, one of the web developers of Alia told me, she’s excited to be able to tell employers who want to do the right thing, “now we have Alia. Here is a concrete thing. Sign up for Alia.”

Magally Miranda is a UCLA Graduate Student in Chicana/o Studies. She received a CSW Travel Grant in 2018.

Comments are closed.