Speculative-Speculative Fiction: Jamie Berrout’s Impossible Trans Literatures

By Tony Wei Ling

When I presented a paper on Jamie Berrout’s Incomplete Short Stories and Essays at a graduate conference last year, I was talking about a book that no longer exists in public.

With trans women’s writing, this isn’t unusual. Berrout has said more than once that “trans women’s writing has the curious property of vanishing almost as soon as it is brought into being.” Curious, but also not. Ordinary.

Incomplete Short Stories and Essays

Incomplete Short Stories and Essays begins with a hyperlinked table of contents, which enumerates eighty-two incomplete stories and marks each with a quoted phrase from the story’s premise. Specific settings and subjects are forgone in place of blurred places and people: “a small border town” and an anonymous, third-person subject, the “trans girl.” Some stories pick up thematically where others dropped off; some zoom out to speculate about a body of trans literature that could never exist. Some stories end mid-sentence.

The collection was originally self-published on Gumroad (a platform for direct sale of writing, music, art, and software), before Berrout removed it from her online store last June, citing a feeling of embarrassed distance –– a sense that the writing was from another time in her life, an awkward and unfinished early work. (Excerpted stories and new additions can be found online.)

The things that make the work potentially embarrassing — its hurried, patchy, unfinished qualities — are the ones that I felt most urgently in writing about it. Incomplete Short Stories and Essays is not only about suicide and exhaustion; it is also sometimes a suicidal and exhausted piece of writing, marked by stories in which the fictional register drops into the writer’s voice, and by stories that are actually barbed, brilliant auto-theory from start to staggered finish. (Maggie Nelson could never.)

“What is this book?” Berrout asks herself in the introduction. “What are these proposals or placeholders for narratives, which often sound more like flirtations with film and television than short stories?”

In that same introduction, Berrout warns readers not to rationalize the numbered fictions into “closed narratives or micro fiction or prose poetry.” The collected stories appear less as literature than as “conceptual or performance art” –– headstones in a “graveyard for trans stories that will never exist.” While not at peace with death, disappearance, or loss, Berrout’s incomplete stories explore the ordinariness of ongoing loss, and the ambivalence of literary writing. Death always lingers as a potential exit, and a routine threat to both the writer and the writing.

Berrout’s trans girls are only barely accessible as reported subjects: she rarely resorts to “vivid” embodied language and narrative evidence that might document characters’ marginalized realities. This compels the reader to believe their realities without the kind of vivid or body-bound proof that might allow readers to see or feel the contours of those realities. If you can’t believe those women, or believe in their phantom worlds, then you are not really capable of reading these partial stories. As I argued in the paper that I presented at UChicago, these flat, sketchy gestures at narrative were a way of demurring from the reproductive work of both radical futurity and liberal humanism.

In writing like this, Berrout drifts away from scripts enforced on trans writing in more traditional publishing contexts, which demand a dramatized, intimate, and/or spectacular encounter with dysphoria and transition1. They demand finish, polish, and proof, in order to stamp the writing with respectable literariness. Instead –– both because she cannot access the gated respectability of traditional publishing, and because she has a distaste for even non-traditional presses’ imposition of cultural capital, Berrout writes temporary stories for trans women.

Trans worlds are easily wrenched away; for trans women of color, that precarious everyday is multiply threatened. Incomplete Short Stories registers this with writing so tenuous and tired that you could punch through it. But its imaginative scope is by contrast — or by consequence — powerfully ambitious. The eighth story conjures an imaginary body of trans literature, wondering what its internal disagreements would offer the young trans girl; the ninth connects (through uncanny, un-confirmed speculation) a young trans man’s suicide to his online business in haunted dolls.

The stories are (were?) amazing, is what I’m saying, and the work they’re explicitly, self-consciously trying to do is that of community-building across distance and difference. Berrout wants trans girls and women not to be alone in the world, or in the act of making their worlds.

The collection doesn’t circulate now, not in any authorized way. Of course, a PDF is in a sense immortal, infinitely reproducible. But it’s a weird and weighted kind of possession that Berrout’s readers have of the book, since its public was always smaller, more intimate, and more personal than that of a book released into the market through traditional means. I haven’t duplicated the book in its entirety since its removal from Gumroad. But I continue to quote from it, and live with it.

The Trans Women Writers Collective Booklet Series

So loss is both ordinary and ongoing; so trans women sometimes vanish their writing, ahead of the universe’s schedule. Berrout’s characterizing gesture could be thought of as a shrug: yes, of course it hurts. The shrug doesn’t deflate the hurt.

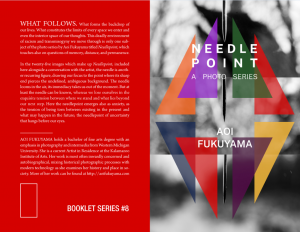

At the moment, Berrout’s new project, a monthly booklet series publishing and paying trans women for their work, is entering its second year of existence. On Twitter and Patreon, Berrout writes openly about the financial tenuousness of the project and the exhausting toll it takes on her, as the underpaid editor and founder. But the series also puts into temporary existence a version of that body of literature the narrators of Incomplete Short Stories and Essays wished for. Trans literature outside of the respectability of elite presses, big and small. Trans literature that you can carry with you. Trans literature that writers got paid for. Trans literature by and for women.

Each booklet introduces a new trans woman’s work; Berrout intends the booklet series as a home and a paycheck for otherwise unpublishable work, or as a place for the re-publishing of work done already, elsewhere. Taken together, the series is one of the most interesting and formally diverse collections of work that I’ve ever read. Sweet, anxious erotica one month and sci-fi stories the next. A photo series of needles. Dense translations. Chapbooks. Repurposed, reconfigured zines.

I intend this post in part as a reflection about my ongoing interest in Berrout, and in part as an introduction to the booklet series. It can only exist for so long, and for a much shorter time than it deserves. At the risk of sounding like a salesman: a subscription is seven dollars a month at the standard rate. You can buy any or all of the previous issues on Gumroad. You can pay Berrout for her work on Patreon or Paypal.

The Editor’s Note to the test issue (#0) of the booklet series — which collects Catherine Kim’s stories about gravedigging and young women’s friendships –– theorizes the empty future of its own project. “But,” Berrout writes, “we don’t write in order to live eternally.” She returns to the shrug as an emotional stance, though she’s deft enough to make it feel like optimism:

We write for ourselves, for the sense of agency and strength and for the bit of cash there is to be had from this work. We could be drawing intricate lines in the sand for an audience and that would be no better or worse than writing if it helped us to survive as writing does. We write for each other too, because each of us has needed trans women’s words and images to find ourselves, to know where we stand—and that goes for cis readers as well. I mean, without us, what would cis people know about themselves? Without our bodies to mark the lines of binary gender’s violence how would they speak or think or live, right? It’s important not to take this too seriously, though. We’re here only for this moment. Let us be as free as we can. Let’s dream of healing for a little while. Or trace the lines towards devouring our demons and destroying police stations, border fences, mansions, prisons, military bases, better yet the logic of exploitation and control that makes them possible. All in good fun.

This Editor’s Note is a manifesto of a different kind: a challenge to take trans writing both more seriously and less. Because we have to let go of those evaluations that put literary quality –– as an end in itself –– above everything else, if we want a hand in making a meaningful “trans literature.” Writing is a form of life, sure, but it’s also a job, a hobby. Something to do with your hands. Something to do to make a community. It doesn’t have to be forever.

Tony Wei Ling is a graduate student in the Department of English at UCLA and was the Recipient of a 2018 CSW Travel Grant.

Works Cited

Berrout, Jamie. n.d. Incomplete Short Stories and Essays. Gumroad.

Berrout, Jamie. 2018. “Editor’s Note” in Catherine Kim’s Collected Stories (BOOKLET ISSUE #0). Trans Women Writers Collective.