Innocence as a Vehicle for Female-Led Satire

By Lillian (Lilly) Lu

We lack the vocabulary to talk productively about female intelligence. We saw this in relation to the 2017 Wonder Woman film, when online debates asked whether the protagonist was written as too naïve or too knowingly sexy, as if those were the only two choices for the heroine. We see this in conversations about sexual assault cases, conversations that fixate on what women do or do not know about their own bodies and desires. In her reading of Diderot’s The Nun, Eve Sedgwick writes that analyses of the protagonist, Suzanne, are too narrowly focused on the binary of whether she knows or does not know her own sexuality. Sedgwick helpfully asserts that “ignorances, far from being pieces of the originary dark, are produced by and correspond to particular knowledges and circulate as part of particular regimes of truth” (25). Sedgwick gets at something crucial: that calling something ignorant—or, as I’m choosing to say in my own project, innocent—is a way to control it, to categorize it, to alienate it from some form of dogmatic “truth” that we must put into question.

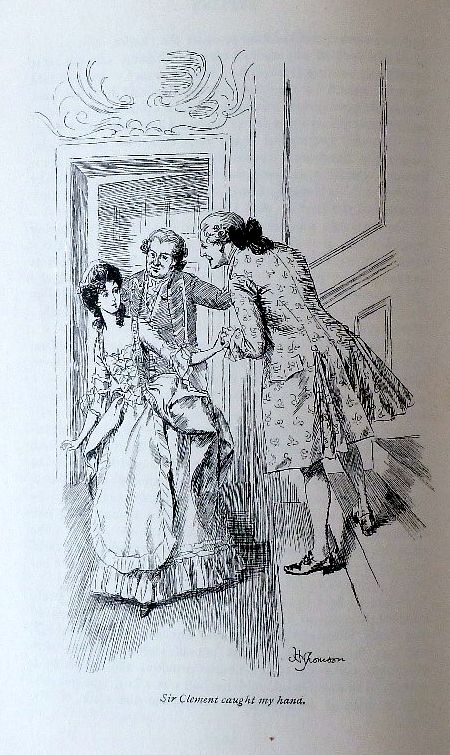

And so we return once more to our inadequate ways of talking and thinking about women’s abilities to know and to understand. Last year, I read Frances Burney’s 1778 epistolary novel, Evelina, for the first time. In the novel, the young eponymous protagonist leaves her countryside home and enters the world of London. There, she is constantly beset by men who gaze at, appraise, and make ridiculous romantic overtures to her. This novel is categorized as a satire, and is often, strangely, described as a satire of Evelina’s innocence. And yet this latter reading strikes me as incongruous to the text. Evelina’s innocence and her intelligence are not, as much of the discourse seems to suggest, diametrically opposed: it is more than possible that a young woman who has been afforded little worldly opportunity could be both innocent and intelligent. In my project, I assert that Evelina’s innocence is a vehicle for the novel’s cutting satire not on female innocence, but rather on male sexual aggression and lack of emotional awareness.

While experience has often been given privilege over the category of innocence, we must examine why we assume experience is richer, more interesting; we must examine why experience is often equated with masculinity and male-led stories, while innocence is equated with femininity and is associated with simplicity, blankness, and most egregiously, stupidity. Counter to these narratives, I find innocence to be an incredibly complex category, one frequently mobilized to invalidate women. It bears meanings of sexual innocence, worldly inexperience, and youth. It is disproportionately attributed to women, children, racial and socioeconomic minorities, and those with disabilities, and yet is co-opted by those in power in narratives that justify the project of empire. My project on Evelina investigates the question of innocence as a powerful lens for satire, a critical mode that allows the protagonist to be dynamic and enables her, ultimately, to laugh at the men around her who are entrenched in their violent ways.

For Evelina is a laugher. About her first ball, she writes that a fop whom she has rejected confronts her after she dances with another: he “assumed a most important solemnity; ‘Give me leave, my dear madam, to recommend this caution to you: never dance in public with a stranger…’ Was ever any thing so ridiculous? I could not help laughing, in spite of my vexation” (47). Though, throughout the novel, she gradually laughs less and less for propriety’s sake—at least in her narration of these events to her guardian—her rants about the persistence of men and their entitlement to her attention, energy, and time continue. In this instance, she is judging those who try to assert power over her, who try to do so by patronizing and cautioning her. Her laughter is powerful, especially in this eighteenth-century London where women are watched always, robbed of the ability to be spectator or arbiter.

Discussions about Evelina do attempt to highlight her intelligence but have a hard time squaring the fact that she is a smart young woman with the fact that she is rather inexperienced in the world. I have noticed that when faced with these difficulties, people pivot the conversation to claims that Evelina is snobbish or elitist, or that the relationship between her intelligence and naïveté is one of contradiction. What I have attempted to show here is that there is no contradiction. If a woman has been sheltered all of her life and has, by the strange logics of the patriarchal system, not been given the opportunities to speak with men on equal terms—to engage in the social world until she is expected to marry—it can hardly be the case that she is all-knowing when she is finally thrust into that world. Being experienced and being intelligent are not the same. The inverse is true as well: being innocent is not the same as being stupid. Having experience is possible only insofar as one is able to have experience, the latter of which has been historically limited in the west to heterosexual, able-bodied, land-owning, white cis-men.

That Evelina calls the men who try to court her—who watch her and impede upon her movement through space—“ridiculous” and that she, yes, gauchely laughs at them, means that she is both innocent about social etiquette and aware that there are rights owed to her. In my project, I assert that these two things do not stand opposed to one another, and when read together, they can, I hope, offer new ways of thinking about female characters and narrators, how they respond and contribute to their worlds, and whether female innocence is something that comes from us, not from them.

Author’s Note: I am grateful to the Center for the Study of Women (CSW) at UCLA for awarding me the spring 2018 travel grant, which allowed me the opportunity to attend the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (ASECS) Annual Meeting 2018 in Orlando, where I presented a conference paper version of my project on Evelina. I was able to receive valuable feedback and connect with other scholars in the field. I plan to incorporate their feedback into future versions of my project.

Lillian (Lilly) Lu is a PhD Student in the Department of English at UCLA.

Works Cited

Burney, Frances. Evelina. Oxford 2008.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Tendencies. Duke 1993.