My 79 Cents: The Productivity Gap Between Male and Female Senior Faculty at UCLA

Olga T. Yokoyama, 2016

Download the PDF version of this report

The analysis presented here uncovers one parameter that reveals a striking gender inequity between male and female senior faculty at UCLA. It shows that the higher women professors rise in their steps, the greater their scholarly productivity. Their male colleagues, by contrast, continue to advance in step virtually without increasing their productivity. The issue is not about equal pay at a given step, but about the amount of work a woman must put in to reach that step, compared to her male counterpart.

The study used the publication records of 10 senior professors (6 men and 4 women) in the Humanities. These faculty members were selected based on the similarity of their academic profiles, which resulted in similar research and publication patterns. This similarity made it possible to compare their scholarly output using the same yardstick. The number of Humanities faculty in a given area of specialization is small and the patterns of scholarly production among these areas can vary considerably. This poses great difficulty if the Humanities are treated as a monolithic whole for the purpose of serious statistical treatment . A quantitative analysis was nevertheless undertaken here, despite the small sample size, in an attempt to provide a measure of objectivity to the extremely challenging task of comparing one Humanities scholar to another Humanities scholar, making use of similarities in the pattern of scholarly production within this admittedly small group. In order to protect the identity of the sample members, some potentially relevant features were not included in this report, such as the years when PhDs were obtained or the years the members were hired and their ranks at the time of hiring. Their area of specialization is not identified for the same reason.

The first step was to determine the categories of scholarly production and the number of publications of each professor in each category. In quantifying productivity only published work was considered. This group published their work in the following categories: authored research books, authored reference books, authored textbooks, edited research books, translated research books, authored research articles (two review articles were included here because by themselves there were too few of them in the sample to count as a category for comparison), translated research articles, book reviews, “other” (introductions to anthologies, ephemera, etc.). Co-authored work was assigned a fraction in which the denominator was equivalent to the number of co-authors (unless the publication contained explicit information about the distribution of responsibilities within the item). These numbers were weighted so as to reflect their relative value in this particular discipline. For instance, a textbook was assigned a value of 60% of a research book, a research article was assigned a value of 15% of a research book, a book review was assigned a value of 5% of a research book, and so on. The weighted values for each person were added together to produce a total academic productivity score for each person. The total productivity of each professor was measured for each step they had held. The calculations were performed manually. Only full professors at Step V or higher were compared for this study. It takes time to advance through the steps; consequently, the scores compared in this study were earned by the faculty members in the sample pool over the course of 21 years (1993-2014). Of the 10 faculty members, only four had reached Above Scale (AS) during the course of this span.

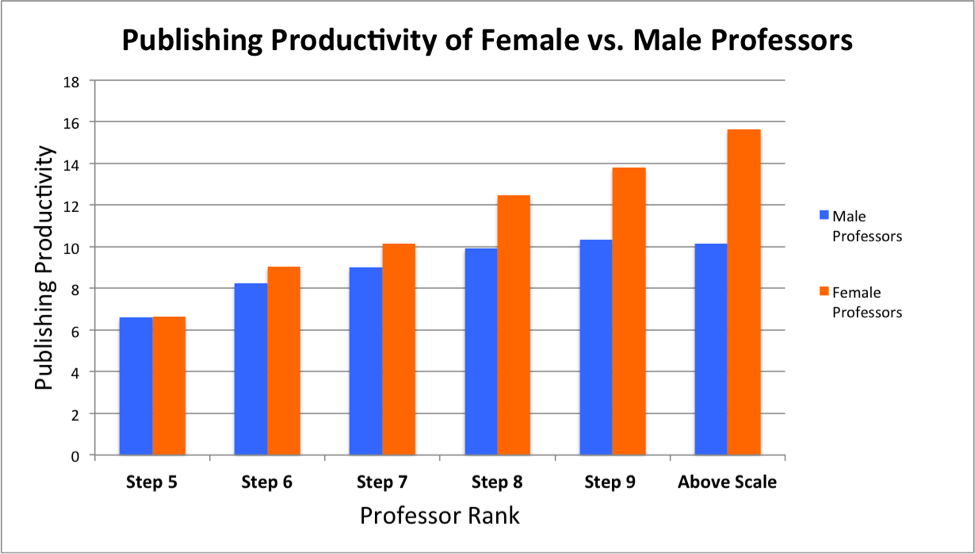

The results are summarized in the following graph:

As the graph shows, the higher they rise in steps, the harder women professors work, compared to their male colleagues. At Step V, the gender gap in production is negligible. But from that point onward, the productivity of men and women begins to diverge. At Step VII, women had already produced as much as their male colleagues ever would even at AS. After Step VIII, the men’s average productivity virtually plateaus. By the time male and female professors reach the highest rank (AS), women are outperforming men by more than 50%.

No qualitative analysis of the publications produced by this group of faculty was undertaken: the assumption was made that UC faculty members at their highest level of accomplishment produced work of comparable excellence. In the category of authored books, the four women as a whole produced 15 books, while the six men produced 10 books. The average length of the books authored by women in the sample was 315 pages, while the average length of the books authored by men was 176 pages. The analysis did not, however, incorporate the length of the publications, which would have given the women an additional edge over the men (thus a book of 800 pages counted as one book, equivalent to a book of 200 pages). It was felt that comparing page counts would make the already somewhat mechanistic approach more vulnerable to the criticism that the analysis favored quantity (i.e. bulk of publication) over quality. Nevertheless, despite the non-inclusion of these two parameters – the quality of the publications and their page length – and at the risk of circularity, it seems reasonable to claim that the clearly emerging pattern itself points to the significance of the results of this in-depth study of the salient quantitative aspects of academic achievement.

To be useful to a wider variety of disciplinary specializations, this method of quantification can be catered to each (sub)field by changing the production categories (e.g. concert performance is clearly a category relevant to music) and their relative weighting. The quality of the publication venues could also be added as a variable, in cases where there might be evidence of significant variability in their quality in the sample under consideration. The overall reliability of the results depends first and foremost on the availability of the information, and then on the careful case-by-case tagging and calculation of the publication records obtained and on the uniform application of the method across all members of the group in question. The variability of the production categories and their complex relative weighting preclude massive across-the-board application of the method; but the process, labor-intensive as it is within each sub-discipline, does make it possible to produce careful comparisons that reflect the specifics of a given field and its publication tendencies over a particular span of time.

The analysis presented here is obviously very limited in scope, and therefore it does not report results on the basis of standard tests of statistical significance. The results obtained, however, dovetail with other quantitative and qualitative reports found in this section (Reports and Initiatives Regarding Gender Equity at UCLA). Especially significant among these reports are those that note a slower rate of advancement of women faculty. Gender Equity Issues Affecting Senate Faculty at UCLA (2000) provides a particularly detailed and statistically rigorous report, pointing to several facts that seem highly suggestive in comparison to my analysis of the situation observed in the highest professorial ranks at UCLA. For example, the report notes comparable salary figures at the assistant and associate professorial levels, but significantly lower figures for women at the full professor ranks across all areas: “[I]t is only at the rank of Full Professor that females earn consistently less than males across academic units” (p. 19). In the Humanities, the difference in compensation in 1999-2000 was approximately $7K (p. 23). In the same year, 40% of males in the Humanities had reached Step VI, vs. only 25% of females (p. 29). According to this report, analysis controlled for year of highest degree and year of hire at UCLA suggests “that women are systematically less likely to have achieved the rank of Full or Step VI Professor, conditional on the length of time since highest degree and time spent at UCLA” (p. 35). In the Humanities, men are 6.8% more likely to have achieved Step VI. Significantly, the report states (p. 37):

Our analysis does not shed any light on the reasons why women appear to advance more slowly through the ranks. More complete interpretation would require detailed information about teaching/administrative assignments, publication records [emphasis mine], research, and family/child care responsibilities. This information was not available to us, although we recommend that it be gathered and analyzed.

Note the mention of “publication records” and the recommendation to gather and analyze them. The current report attempts to explore precisely that, by correlating of gender with step and with detailed information about publication productivity.

Two years later, Promoting Faculty Diversity at UCLA (2002) comments à propos the new data base created under the auspices of the then new position of Director of Academic Resource Information: “With a new database and analytical support, it is UCLA’s intention to delve more deeply to understand the basis of and factors contributing to both salary and advancement rates for men and women” (p. 14). To the best of my knowledge, what I present here is the first such attempt “to delve more deeply to understand” the gender gap, specifically with regard to the publication records of Humanities senior faculty within a particular specialty, by correlating them with faculty advancement through Steps V and higher.

The comment about women’s slower progress through the ranks is repeated in UCLA Gender Equity Summit Report (2004) (p. 14). Significantly, this report recommends that “Each department should have a written policy on its expectation for stages of promotion” (pp. 5, 9). Since every case of advancement begins in the candidate’s home department, the results of the current study suggest a potential impact of differing expectations departments have towards their men and women faculty. What drives senior women’s productivity may be the women’s own perception that “their scholarly contributions are scrutinized more carefully or evaluated less favorably than equivalent work of their male colleagues” (p. 15). The report presented here shows that senior women (in the specialty in question) do indeed produce more than men, and thus it indirectly supports this perception of unfairness on the part of the women (if not actual unfairness towards them).

Having performed this exercise, I echo the UCLA Gender Equity Summit Report: I, too, would like to recommend that each department examine the research and publication (or other relevant achievement) profile of its specialty (or specialties), so as to reach agreement on the list of categories and their relative weight, which could then be made available to department members as “a written policy of its expectation for stages of promotion”. This would not only address the vague sense of a double standard held by women faculty (and now confirmed at least for the group analyzed here), but it would also considerably simplify the task of preparing dossiers for departmental ad hoc committees. (As disciplinary expectations change with every generation, the list of categories and their weighting should be revisited every 15 years or so, perhaps being timed to every second 8-year review.)

If the widely-held (self-)perception that women “may be unduly burdened with committee and departmental assignments, often in roles of low visibility, while at the same time, very few women serve on the most important committees” (UCLA Gender Equity Summit Report, p. 15) is eventually examined critically and proves to be accurate, and if the results of this study suggesting that women faculty work harder than men in their publication productivity are supported by similar studies for other subareas, then a gender gap will be shown to exist in both the research component and the service component of our profession. Adding a comparison of male and female faculty’s performance in teaching would complete the picture, as far as the three areas of faculty performance relevant for advancement are concerned. Labor-intensive as it is, continuing this work and expanding it to all of three components is the only sure way to establish convincing grounds for taking action that would lead to gender equity.