Women and Power in Postconflict Africa

“Change between gender regimes can be uneven. Thus, we have sometimes seen women gaining political power through quotas in legislatures, judiciaries, and government positions, with less change in other spheres such as the military and police. It appears that women found it easier to make inroads into key political and economic institutions, but much harder to gain a foothold in religious and traditional institutions outside the state and market.” — Aili Mari Tripp

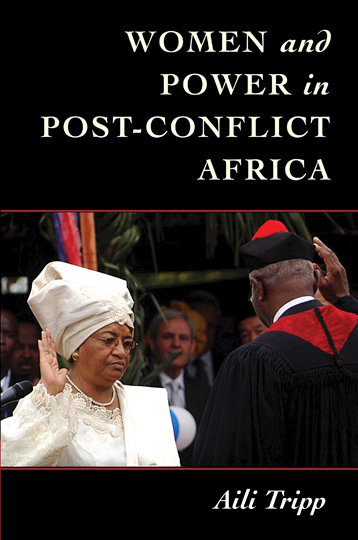

In her new book, Women and Power in Postconflict Africa, which is part of the Cambridge Studies in Gender and Politics series, Aili Mari Tripp presents research on the gender-related consequences of the decline of major conflict in 17 countries in Africa over the past 20 years. It explains why postconflict countries in Africa have significantly higher rates of women’s political representation compared with countries that have not undergone major conflict. It also looks at why these countries tend to have been more open to passing legislation and making constitutional changes relating to women’s rights.

In her new book, Women and Power in Postconflict Africa, which is part of the Cambridge Studies in Gender and Politics series, Aili Mari Tripp presents research on the gender-related consequences of the decline of major conflict in 17 countries in Africa over the past 20 years. It explains why postconflict countries in Africa have significantly higher rates of women’s political representation compared with countries that have not undergone major conflict. It also looks at why these countries tend to have been more open to passing legislation and making constitutional changes relating to women’s rights.

The books “focuses primarily on three case studies, Uganda, Liberia, and Angola, which are examined against cross-national comparative data pertaining to women’s rights influences on opportunity structures (peace agreements and constitutional reforms) as well as outcomes (numbers of female political leaders and women’s rights legislation). It traces their evolution, documenting the commonalities and differences in causal mechanisms that gave rise to these developments. It looks at these cases against the backdrop of structural changes in Africa, including the end of conflict and political liberalization. Uganda and Liberia were more successful than Angola in advancing women’s rights. The contrast between these countries allows us to identify crucial factors that explain the causal mechanisms at work in postconflict countries. ”

Tripp notes that her characterization of a decline in conflict does not imply that violence has ended, nor does it imply, as claims, that peace is “the absence of war” (Page Fortna 2004): “Numerous forms of violence continue in postconflict contexts, particularly for women, who continue to face heightened insecurity in their homes or communities. Sometimes, the forces that are supposed to be ‘protecting’ civilians, like peacekeeping troops, have themselves been sources of insecurity and gender-based violence. Recent research suggests that the death rate for women is higher than for men after the conflict is over.” She does, however, stat that “there were significant changes in the gender regimes, particularly in political institutions, but also in other institutions in countries affected by major conflict, and some progressed further than others.”

In a review on the blog of the London School of Economics and Political Science, Alice Evans, Lecturer in Human Geography at the University of Cambridge, noted that “Women and Power in Postconflict Africa is everything one might hope for: rigorously researched (in-depth qualitative, process-tracing complemented by cross-national regressions), highlighting global parallels and theoretically significant.”

On April 7, 2016, Tripp will be giving the keynote address at this year’s Thinking Gender, CSW’s annual graduate student research conference. Register today!