CSWAC Corner: Tria Blu Wakpa

Get to know our CSW Advisory Committee (CSWAC) members through CSWAC Corner! We are proud to have an advisory committee made up of feminist scholars working in various fields from gender studies to public health to film and television.

Get to know our CSW Advisory Committee (CSWAC) members through CSWAC Corner! We are proud to have an advisory committee made up of feminist scholars working in various fields from gender studies to public health to film and television.

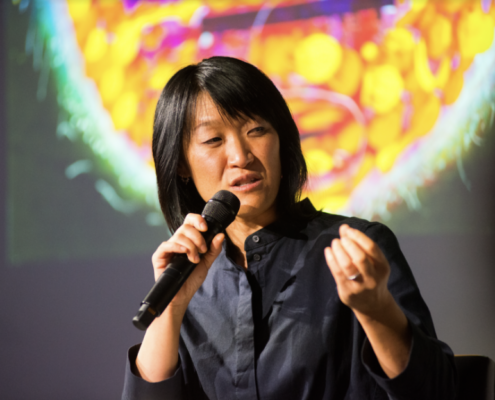

Meet Professor Tria Blu Wakpa

Pronouns: she/her/hers

Department: World Arts and Cultures/Dance

Tria Blu Wakpa is an Assistant Professor of Dance Studies in the Department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance. She is also affiliated with the American Indian Studies Center and the Center for Community Engagement, serving as the Community Engagement Council representative for the Institute of American Cultures.

What does your current work consist of?

My research and teaching center community-engaged, decolonizing, and dance studies methodologies to examine the politics and practices of dance and other movement modes—such as theatrical productions, athletics, and yoga—for Indigenous peoples in and beyond structures and institutions of confinement.

Currently, I am focused on finalizing my book project, Native American Choreographies in Confinement: Bodies as Battlegrounds, Institutions as War. The book historically and politically contextualizes dance, student theatrical productions, basketball, Lakota cultural curriculum and ceremony, and yoga at four sites on Lakota lands: a former Indian boarding school (1886-1972); men’s and women’s prisons (1889-Present and 1995-Present); and a tribal juvenile hall (2005-Present). In the book, I theorize how diverse institutions of confinement have sought to manage Indigenous bodies and movement modes, while Native people have enacted practices to sustain, generate, and transmit vital knowledge through their performances and gatherings. Such an approach illuminates Indigenous bodies and movement practices not only as targets, but also as sites of possibility, wellbeing, and survival—even from inside the settler state’s most repressive institutions. In addition to my book project, I am a Co-Founder and the Editor-in-Chief for Race and Yoga, the first peer-reviewed and open-access journal in the emerging field of critical yoga studies.

I have taught a wide range of interdisciplinary and community-engaged classes at public, private, tribal, and carceral institutions and collaborated with Lakota and California tribal people on exhibitions and performances. In 2022, I created a community-engaged course titled, “The Politics and Possibilities of California Tribal Dance,” for which I was the first Assistant Professor at UCLA to receive the Chancellor’s Award for Community-Engaged Research. The course collaborates with California tribal individuals and representatives from four different nations: the Tongva, the Chumash, the Costanoan Rumsen Carmel Tribe, and the Winnemem Wintu. Students in the class conduct research, which supports the dance revitalization efforts of these California tribal communities. The Winter 2024 iteration of the class culminated in an intertribal dance gathering, held at Wishtoyo Chumash Village in what is often referred to as Malibu, California. This intertribal dance gathering was made possible by a 2022 Living Through Upheaval Grant from the University of California Humanities’ Research Institute, an Instructional Improvement Grant from UCLA’s Center for the Advancement of Teaching, and a Radical Teacher Fellowship from the University of Pittsburgh. Already this collaboration with our California tribal partners has resulted in a co-written publication with UCLA World Arts and Cultures/Dance doctoral candidate, Sammy Roth: “Performativity, Possibility, and Land Acknowledgements in Academia: Community-Engaged Work as Decolonial Praxis in the COVID-19 Context,” which was published in 2023 in Performance Matters. A second article about this work, “Toward Becoming Good Relatives: Not-Dancing to Center Indigenous Presence in the Dance Classroom,” was co-written with Roth and another UCLA World Arts and Cultures/Dance doctoral candidate, Miya Shaffer, and is forthcoming in Performance Matters.

Beyond UCLA, I am also active in the larger Los Angeles community. In 2023, Mayor Karen Bass appointed me to the Los Angeles Cultural Affairs Commission. I currently serve on three boards in Los Angeles that further culturally relevant education and opportunities for Native children in grades K-12. Above all, I am the mother to two children, ages seven and six.

What are you recently proud of/excited about in your career so far?

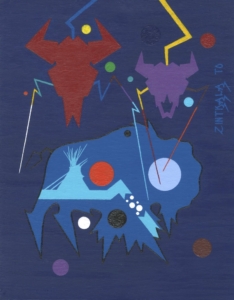

I am most proud when the people and the communities whom I am writing about view my writing as a valuable and an accurate representation of themselves and/or their ancestors. Over the years, I have learned that respectful and reciprocal relationships—what scholar Shawn Wilson refers to as “research is ceremony”—are powerful. Such relationships contribute to the wellbeing of the people I am working with while strengthening my analysis by adding insights that would have otherwise been inaccessible without such collaboration. In December 2022, I published an essay titled, “From Buffalo Dance to Tatanka Kcizapi Wakpala, 1894-2020: Indigenous Human and More-than-Human Choreographies of Sovereignty and Survival,” in American Quarterly, a top-tier academic journal. The article presents the first extensive study of Buffalo Dance, one of the earliest films to depict Native Americans. It also features the words and artwork of George Blue Bird, who has been imprisoned for over four decades and is a direct descendent of one of the dancers in the 1894 film. George and his relatives were very pleased with the article and its recognition of their ancestor Parts His Hair’s contributions. In 2023, the article won the American Society for Theatre Research’s Gerald Kahan Scholar’s Prize “for the best essay written and published in English in a refereed scholarly journal or edited collection.” I feel moved and motivated knowing that by collaborating with Native experts like Blue Bird I can create work that is both meaningful to them and the academy.

Other than your current research interests, what other fields would you be interested in exploring with time given?

My research is already very interdisciplinary. For instance, I locate the book project at the intersection of dance, theater, cinema, athletic, yoga, Native American, Indigenous, human and more-than-human, education, prison, and religious studies.

It has become very apparent to me that because of the Eurocentric construct of Cartesian dualism, many people, even other academics, frequently disregard dance studies and fail to take our work seriously. Cartesian dualism is the false and pervasive perception that the “mind” is separate from and superior to the “body.” Due to Cartesian dualism, it can be very challenging for people outside our field to understand what dance studies scholars are doing or why it matters. One of my mentors at UCLA, Distinguished Research Professor Susan Foster shared with me that she often explains dance studies to people by describing our field as like art history for dance. A primary methodology in dance studies is “choreographic analysis,” which applies close readings to bodies and movements to reveal critical knowledge, like how one might analyze a poem. To do a choreographic analysis well, a scholar must know the history and politics of a movement practice and the space and time in which it occurs. In other words, although our work might be marginalized, dance studies scholars are frequently well-versed, engaging with, and expanding upon critical theory, political theory, critical race studies, gender and sexuality studies, post/decolonial studies, American studies, history, environmental studies, and many other fields to situate the histories and politics that undergird movement practices. In addition to this this context, they are analyzing dances and other movement forms!

Further, I want to underscore how powerful dance studies is by sharing an insight that my friend and mentor, George Blue Bird, whom I previously mentioned, gifted me. At one point while writing the book project, I was grappling with centering dance and movement practices within the contexts of confinement. How could I ethically justify writing about dance and movement practices as forms of resistance when violence was so pervasive in these spaces, such as a former Indian boarding school and prisons? Yet, when speaking with George, he told me that Lakota mothers would encourage their children to play within genocidal contexts, because given the life and death stakes, their moments of joy were vital. In other words, George reminded me that dance and movement practices are not less important within situations marked by immense violence, instead, they can be even more important.

All this said, I am interested in gaining more familiarity with the field of neuroscience. I am inspired by the work of Dr. Michael Yellow Bird and want to learn more about how movement and contemplative practices impact the brain and can contribute to decolonization on a bodily level.

What is a motivational piece of advice that you’d recommend to others starting out in your field of interest?

I tell the students whom I supervise that while other faculty and I can offer them valuable career advice, ultimately, they should pursue the trajectory that they think makes the most sense for them. I tell my students this based on my own lived experiences, which have illustrated that pursuing activities beyond what is often considered the prescribed academic path can powerfully enhance one’s thinking, writing, and career trajectory, even if it is not clear exactly how or why at the time.

For example, when I was in graduate school at UC Berkeley, I felt compelled to perform in Indigenous-led dance performances. Some faculty felt I should not be doing so and should instead solely focus on finishing my dissertation. However, it was through these dance practices, performances, and gatherings that I gained new insights, which instrumentally shaped the thinking and theorizing I was doing in my dissertation at the time and ultimately my book project today. Through this dancing process, I also strengthened relationships with faculty from other departments and universities who continue to serve as strong mentors for me. One of these faculty members, Professor Jacqueline Shea Murphy, eventually became my official mentor for the 2017 University of California President’s Postdoctoral Fellowship that I received.

Then, after I was offered the job at UCLA, one of my mentors from graduate school who had encouraged me to focus solely on the dissertation, remarked to me that had I not participated in the dancing, I might not have been as well suited for the position in dance studies. At the same time, my mentor had been correct in that it was essential to finish my dissertation, or I would not have been qualified for the position at all! But that was an important learning moment and reaffirmed for me that while it is important to consider your mentors’ constructive advice, it can be equally important to trust your instincts and become the scholar you want to be.

Where can we find you on social media?

People are free to reach out to me on social media. But first and foremost, I’m a mom, so my social media predominantly features photos of my little ones, our pet dog and turtle, and our activities together. I intersperse these posts with updates about my research, teaching, and community engaged projects. Because the personal is political, it all interconnects. I have even included my children’s insights in my peer-reviewed publications!

People can also connect with Race and Yoga journal on social media. I am a Co-founder and the Editor-in-Chief for Race and Yoga. UCLA doctoral candidates in the Department of World Arts Cultures/Dance, Ali Kheradyar and Sammy Roth, serve as editorial assistants for the journal.

X: @tria_blu_wakpa

Instagram: @triabluwakpa

Facebook: tria.blu.wakpa

X: @RaceandYoga

Instagram: @raceandyoga

Facebook: raceandyoga

Photo Captions:

Photo 1: Professor Blu Wakpa in Kaufman Hall with her two daughters, Hante and Azilya. Photo credit: Shandra Fleming Photography.

Photo 2: Tina and Jessa Calderon, Tongva and Chumash artists and Culture Bearers, who have collaborated with Professor Blu Wakpa for five years. The Calderons co-organized and participated in an intimate California Tribal Gathering at Wishtoyo Chumash Village in March 2024. Photo credit: Guido Frazzini.

Photo 3: Image of an untitled painting by George Blue Bird (2021). Professor Blu Wakpa included this image in her essay, “From Buffalo Dance to Tatanka Kcizapi Wakpala, 1894-2020: Indigenous Human and More-than-Human Choreographies of Sovereignty and Survival,” which was published in American Quarterly in December 2022. The article discusses Blue Bird’s ancestor, Parts His Hair’s choreography in the film Buffalo Dance (1894). This image of Blue Bird’s painting was also featured as the cover for the journal issue.

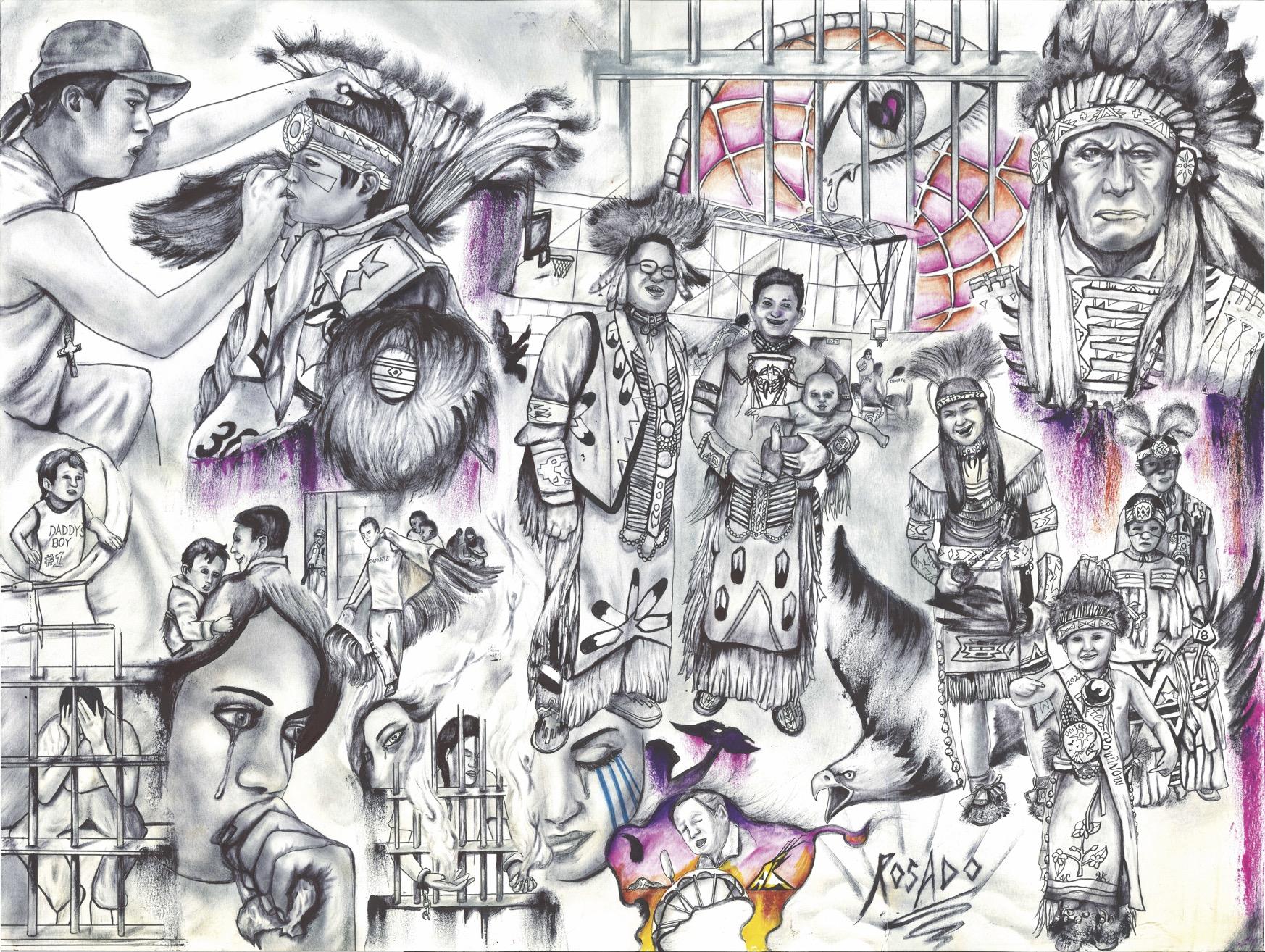

Photo 4: Image of an untitled drawing by Alexander Rosado (Oglala Lakota, 2021). The drawing depicts scenes from powwows held in prisons on Lakota lands and was created for Professor Blu Wakpa’s book project, Native American Choreographies in Confinement: Bodies as Battlegrounds, Institutions as War.

Photo 5: Professor Blu Wakpa with her 2023 Gerald Kahan Scholar’s Prize from the American Society for Theatre Research. Photo credit: Shandra Fleming Photography.

If you are a CSW Advisory Committee member who would like to be featured in CSWAC Corner, please fill out this Google Form