Long Live Lunch @ Bunche: The Kitchen Committee and The Social Reproduction of Striking Labor Power

By Da In Choi and Rosie Stockton

In November, the first thing you’d see – rain or shine – when you walked to the Bunche Picket Line was a set of long tables cobbled together, overflowing with food. During the picket shift change, the self-organized Kitchen Committee would hop on the speaker, announce the meal for the day, and a line of striking workers would form, snaking around the front of the Bunche Hall Plaza. From day one, the offering at lunch seemed endless: enchiladas, salads, casseroles, pastas, falafel, quiches, beans, pizza, sushi, risotto, dal – the list went on.

In order to consistently serve hundreds of people for 40 days, the Kitchen Committee reorganized and reclaimed all the fridges, TA offices, and bathrooms in the social science corner of the UCLA campus. Nicola, a member of the Kitchen Committee, talked about how reappropriating TA offices, which were supposed to be used for administrative work, into kitchen spaces and pantries gave them a sense of power. The apartment of a fellow member, Amber, transformed into a base for organizing kitchen work. The UAW leadership did not recognize the students’ kitchen as a place of organizing. Although they approved remote shifts, their priority was still on students’ participation on campus. However, many graduate students and community members brought food they made in their kitchens, dishes, and supplies, which sustained strike efforts. Disrupting private/public binaries and what constitutes labor and its refusal by using students’ apartments, vehicles, and campus buildings collectively built alternative spatial politics and logistics. The Kitchen Committee created complex pantry inventory and menu prepping with elaborate spreadsheets that also figured as the base of their logistics. Their logistics followed not the extractive logic of the UC, nor the sanctioned UAW leadership model of organizing power. Rather, the Kitchen Committee’s logistics emerged out of striking students’ needs and desires, and took the form of mutual aid.

Aside from the plethora of food spilling off the table at the Bunche picket line, in the midst of a historic labor strike with over 48,000 academic workers, the conversation about how striking labor power could be reproduced and sustained was at the level of a mere murmur. When we wandered to other picket lines on campus, we noticed the snack table would have donuts, coffee, and pizza, if they were lucky. As the strike went on and conversations about how to measure strike power emerged, we found that the Bunche picket line was particularly dedicated to demanding the bargaining team hold our original demands: COLA4ALL, cops off campus, disability justice, and protections for international students. Kitchen Committee member DH said that there were conversations around bringing the Kitchen Committee to other picket lines such as engineering. The engineering picket line also expressed interest in eating and working with Bunche, wondering how the dynamics of the strike were affected by the presence (or absence of) nourishment and care for the living striking bodies.

In the lacuna of conversation about reproducing power and feeding striking students, conversations about how striking power was “waning” on the picket line began to emerge. This concretely affected the bargaining strategy at the table to the dismay of thousands of workers who insisted they would remain on strike to meet our original demands, and who were unwilling to concede because of rumors of waning power. The UAW leadership’s method of measuring power by counting productive bodies on the picket line, and dismissing reproductive labor, illustrates how UAW leadership abided by capitalist logic and embodied its contradictions. Feminist political scientist Nancy Fraser argues that the “crisis of care” in contemporary society arises from capital’s need to accumulate at the expense of social reproduction. Reproductive labor, an activity such as cooking and cleaning that sustains individuals and communities on a day-to-day and intergenerational basis, had long been elided in the labor and union organizing history as secondary to the cause. Michael Buse, another member of the Kitchen Committee, said this was quite telling as the UAW leadership initially told students that they would provide granola bars and water, and that striking workers were responsible for otherwise feeding themselves. In addition, it was made clear that no food donations were allowed, outside the official UAW Hardship fund. Despite requiring strikers to work 20 hours a week on the picket line, many students reported that granola bars and water bottles were only provided until day 8 or 9. In response to this, many rank and file members, who recognized the importance of food, insisted on organizing for good eating. It was this vocalized need (and want) that led to the Kitchen Committee coming together, to feed people through unofficial channels. The Kitchen Committee embodied alternative politics that sprang from emphasizing life that disrupts capital’s constant demand for movement and productivity.

It was no great surprise that a kitchen funded entirely from mutual aid donations (not UAW approved, in fact) was a space of profound intimacy, power, and life on the picket line. Nicola said they did not see the Kitchen Committee’s work as unrecognized labor – the people who truly mattered to her showed appreciation. When Nicola was at the kitchen table, the students who were there to eat lunch laughed at the jokes, rejoiced to see the food they loved, and thanked them. For Nicola, the UAW and the university were not the ones they were seeking recognition from in the first place. The intimacy and joy that arose from these everyday encounters and joy was what sustained the strike. As Amber put it, the “immense labor taken on by every member of the Kitchen Committee was driven by a sense of obligation to one another, and to our colleagues on strike, that felt familial. And in that sense, it extended my understanding of family—or even my broader sense of belonging—through these emerging kinships.” Furthermore, so many community members showed up: friends of fellow students, advocacy groups, small businesses, faculty members, and their networks. They showed “forms of care that exceed[ed] the genre of contract [that] both the union leadership and university remain[ed] incapable of fulfilling.”

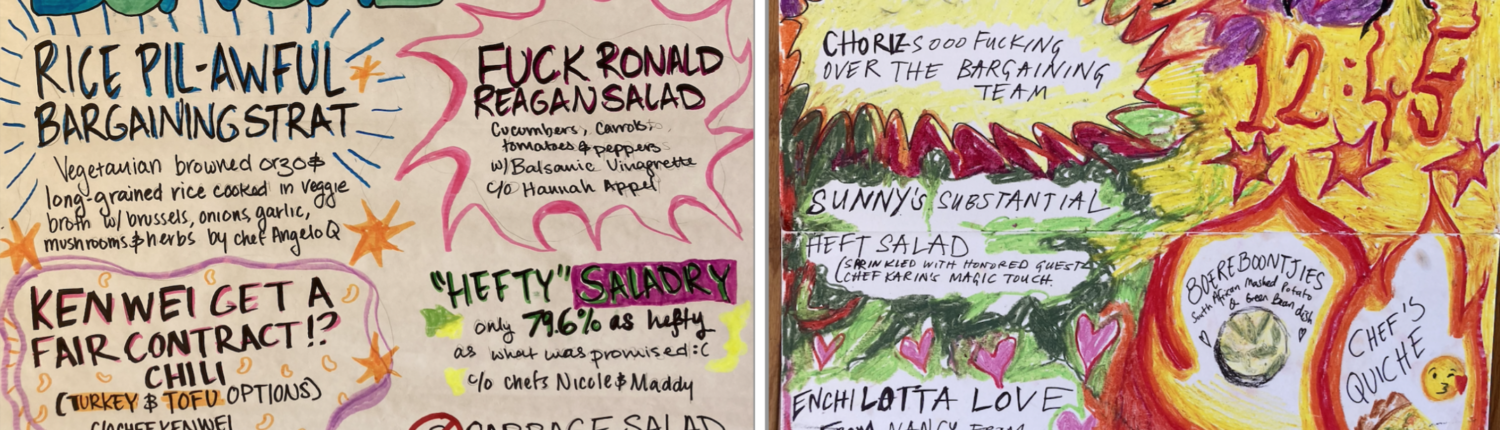

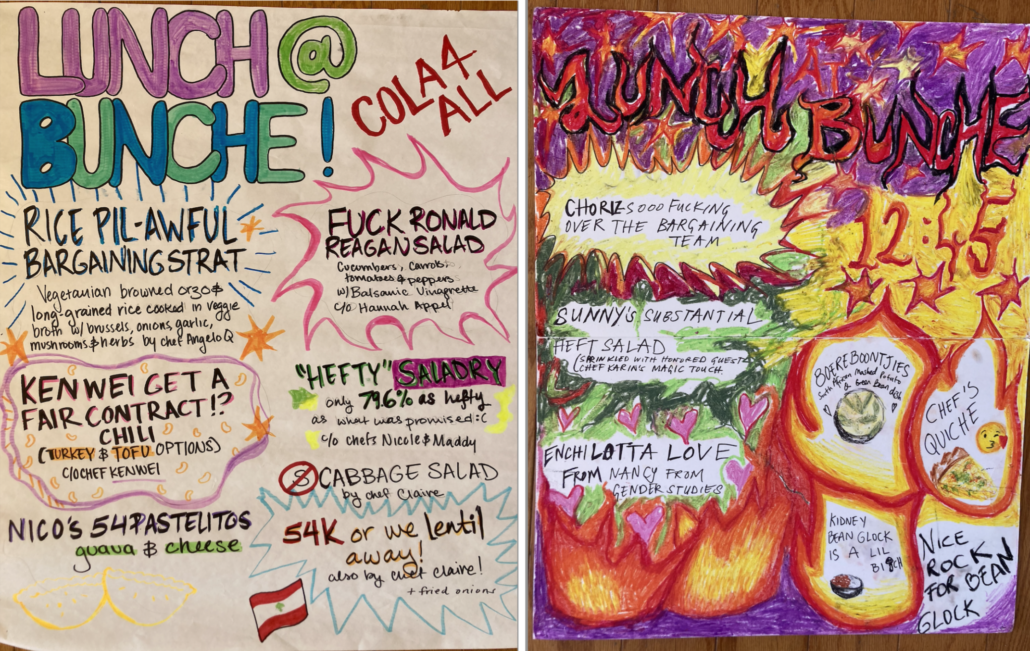

Echoing histories of mutual aid-based food programs that exceeded institutional support, we might see the Kitchen Committee’s labor as the most threatening and revolutionary form of activity of all: the construction of new systems of care and support that exceeded what was expected, legitimated, and recognized by either the UC or the UAW leadership. The forms of care practiced by the Kitchen Committee, according to Nicola, “reiterated values of solidarity and collectivizing despite having been siphoned off by bureaucratic relationships.” As the strike went on, lunch became more and more a focal meeting point of the day. Amidst the pressure and specter of docked wages, many students we spoke to at the Bunche picket line would come specifically for lunch—the prospect of free food, a space to process the snarled strike dynamics and bargaining process, and the laughter sparked by the iconic Kitchen Committee menus made long, physical, and sometimes rainy picket line shifts enjoyable. Though non-UAW approved signs were technically not allowed under UAW striking guidelines, the menus announcing the meal for the day were some of the only unofficial UAW signage seemingly tolerated at the picket line, in addition to signages brought in by COLA4ALL organizers. The menus were drawn on a big poster board at the beginning of lunch, decorated with drawings and puns. As time went on, the food items on the menus began including puns that embedded critique of the greed of the UC, as well as many striking workers’ disappointment with the union leadership bargaining strategy (“EAT THE REGENTS RISOTTO,” “VEGGIE FRIED RISE UP AND DEMAND A FAIR CONTRACT,” “COPS OFF KALE SALAD,” and “CHORIZZOOOO FUCKING OVER THE BARGAINING TEAM). As Samyu said, “the Kitchen Committee began filling that gap of where the University and UAW leadership could never provide a truly revolutionary politics.”

The Kitchen Committee is still continuing its program—acknowledging the fact that students’ material conditions have not changed. Starting Thursday, January 26, 2023, as the winter quarter begins, the Kitchen Committee is renewing their commitment to feed the campus community. Open to all, the Kitchen Committee is also commencing delivery services to those who cannot be on campus, to reimagine “our connection to communities.” Despite the formal “end of the strike” and ratification of the contract that denies living wage and access needs for students, the continued presence of the Kitchen Committee points to how their work still sustains us—students, faculty, and community members—today. As Amber beautifully put it, the Kitchen Committee confirmed for them that “another university… exists. We made a small, delicious world—it became a place that I could go in the morning, where I could see all my loved ones, and cook with them.”

We want to thank Michael Buse, Amber Chong, Samyu Comandur, Nicola Chávez Courtright, and D.H. We for generously giving us their time to share their insights on the Kitchen Committee. The Kitchen Committee is planning on doing monthly lunches at Bunche so please consider donating or ordering the meals here.

Bibliography

Fraser, Nancy. “Contradictions of Capital and Care.” New Left Review 100 (2016).

https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii100/articles/nancy-fraser-contradictions-of-capital-and-care.