A Young Woman’s Notes on the 1918–19 Influenza Pandemic

By Kathleen Sheldon

Some years ago, I inherited a small diary kept by my great-aunt, Sylvia Thankful Eddy. Most of the diary concerned her travel and first two years of residence in Turkey in 1919–1920, where she was a Red Cross nurse. She pursued nursing training and applied to work as a nurse overseas as an escape from the expected course of marriage and family. Recruited by the Near East Relief organization, she remained in Turkey until the 1940s as a missionary affiliated with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Her story adds a young woman’s ideas to our collective knowledge about the impact of the influenza epidemic one hundred years ago.

Some years ago, I inherited a small diary kept by my great-aunt, Sylvia Thankful Eddy. Most of the diary concerned her travel and first two years of residence in Turkey in 1919–1920, where she was a Red Cross nurse. She pursued nursing training and applied to work as a nurse overseas as an escape from the expected course of marriage and family. Recruited by the Near East Relief organization, she remained in Turkey until the 1940s as a missionary affiliated with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Her story adds a young woman’s ideas to our collective knowledge about the impact of the influenza epidemic one hundred years ago.

As we continue to try to move forward during our own pandemic, I went back to her diary, a small pocket-sized book, where she noted daily events and occasional thoughts, beginning on January 1, 1919. I was curious about the observations of a young woman—a trained nurse—concerning the international impact of the flu. I extracted the entries that directly commented on the flu or on illness she does not identify as the flu. The entries here have been transcribed and minimally edited by me from her handwritten diary.

During the first few days of 1919, Sylvia was finishing a tour of duty in Nitro, West Virginia, the location of a World War I munitions factory. The factory was closing due to the end of the war and the loss of personnel to the flu. She did not refer to any illness at this point, but a history of the town mentions the impact of the flu in accelerating the plant closure.[1] Sylvia returned to her family in Simsbury, Connecticut, and at first, she noted participating in social activities without referencing the flu. Then, she wrote, “Went to Hartford with Father and [my sister] Olive … went to the movies. Came home and found George quite sick with the ‘Flu.’ So I had to start in doing a little nursing” (January 10, 1919).[2] Throughout the two years covered in the diary, she prioritized describing social occasions rather than her nursing responsibilities.

Over the next few days she continued, “Spent the day taking care of George” and “George better” (January 11 and 12, 1919). As her brother-in-law’s health improved, she moved on to care for another family in Simsbury, “Dr. Carver came and as George was better [I was] asked to go and take care of Mrs. Harry Eno. Mr. + Mrs. Eno and the boy all in bed with Flu. … Frank and Selina Daly were there keeping house” (January 13, 1919).[3] As a young woman without her own husband and children, she was available to act as a live-in nurse for family and friends. She did not mention any payment, suggesting that her nursing expertise was provided on an unpaid basis. The doctor dropped in to check on family members, but she supplied the round-the-clock care.

While continuing the local nursing care, she received news that renewed her hope of leaving for the Middle East: “Still at Enos received a telegram from Red Cross asking me to go to Armenia + Syrian relief in the Near East. Wired acceptance.” She was freed to take that desired assignment, as “They got a nurse at Enos so I could come home. Slept all day” (January 14 and 15, 1919).

During the following weeks, she prepared for her journey. She spent several days in New York City, where she purchased items needed for Turkey and engaged in a series of social activities. She mentioned movies and plays she attended and named restaurants where she dined out with friends. She did not at any time refer to wearing (or not wearing) facial masks, worrying about being in proximity to crowds, or any other flu-related practices or behaviors. These issues were contested during the 1919 flu epidemic just as they are in 2020–22, but she never indicated whether she agreed with such restrictions or knowingly flouted them.[4] Eventually she boarded her ship along with dozens of others traveling with the Near East Relief.

While on the ship, she became ill, and that illness was incapacitating. She did not refer to her illness as the flu.[5] She wrote, “Felt sick cough etc., reported to Mr. Smith, sat on deck in steamer chair finally went to bed” (February 18, 1919). “Feeling worse taken to Sick Bay had a nice upper bunk. We passed the ‘George Washington’ with President Wilson on board. The boats exchanged rockets. I had an earache, Dr. Richards punctured the drum” (February 19, 1919).[6] She continued to make daily notes, “Still in Sick Bay;” “‘Sick Bay,’” and “A great day on board so they told me, athletic contests between Y.W.C.A. and A.C.R.N.E. [American Committee for Relief in the Near East], tugs of war etc., also various stunts by the sailors” (February 20, 21, and 22, 1919). Throughout her diary she exhibits a fun-loving personality, in this instance, even when she was unable to be present due to her severe illness.

When the ship arrived in Europe, Sylvia remained very ill, and she was not allowed to disembark. As she managed to record, “Arrived at Brest early this morning as I had pneumonia, had to stay on board; got to go back to New York. Everyone came in to say good-bye and sympathize. I was too sick to care.” The next day she wrote only, “‘Sick Bay’” (February 23 and 24, 1919), though that entry was followed by a bit more excitement, “All hands busy coaling, troops coming on board [military returning from service in WWI], 10,000 27th (New York’s own) going back. I was moved to a dandy big outside stateroom on D Deck. Everyone is so lovely to me” (February 25, 1919).

For the next few days, she only noted that the ship had “Left Brest at 1:30 p.m.” and was “On the Atlantic,” while she was “Still in bed” (February 26, 27, and 28, 1919). She did not add any entries for March 1, 2, or 3, and returned to her diary with this note, “On deck for a little while still feeling very shaky” (March 4, 1919). She finally began to recover, more than two weeks after she initially went to sick bay.

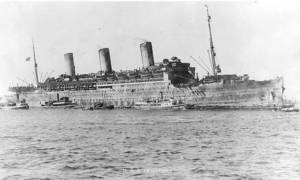

She noted the ship’s return to the US with her usual appreciation of experiencing a lively event, “March 6 a never to be forgotten day. I was able to be dressed and on deck. At eight a.m. the airplanes, decorated tugs, ferry boats etc. started coming way down the bay to meet the ship. The bands all played ‘Hail Hail the Gangs all here,’ etc., quite thrilling especially when the boys recognized anyone on board the tugs. From every building there were crowds watching and cheering, flags flying, and confetti and streamers were much in evidence as it was 9,000 of the 27th, New York’s own, on board” (March 5, 1919).

Source: Naval History and Heritage Command, Title: USS Leviathan

Description: (ID # 1326) Entering New York Harbor in March 1919, with 8,000 troops of the 27th Division on board. Photographed by Enrique Muller, Jr., New York. Courtesy of Harold B. Feile, 1970. US Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph.

Catalog #: NH 70166. Thank you to Earle Spamer for locating this photograph for me.

The next few weeks have few entries. She mentioned her return to Simsbury, “Arrived home 9:30; mother and dad met me in Hartford. Robert [her brother, Robert Collins Eddy], thanks to the kindness of Col. Barlett and General [George H.] McManus, met me on board the Leviathan. Still feeling shaky but able to travel home. Gen. McManus lent us a car so we missed [her friends] “Harrie” and Tom at the gate” (Mar. 6, 2019).

At this point Sylvia had been ill for sixteen days. She continued to recover once she was back in Simsbury, though there are no further entries until the end of the month, likely indicating that her illness lasted for as long as six or seven weeks. She only returned to her diary to note the death of her sister-in-law, a young mother. She did not mention the flu, but that was most likely the cause of death. “Grace died early this morning. [Her two younger sons] Donald [age 6] and Julian [age 10] were here all day” (March 27, 1919).[7]

She eventually recovered and traveled to Europe in June 1919. She reached her post at the American Hospital (officially the Azariah Smith Memorial Hospital) in Aintab (now Gaziantep), Turkey, in November and began her work as a nurse. Her friend, Louise Clark, another nurse, fell ill, and Sylvia described that illness as the flu, though that did not seem to warrant isolation, nor the suspension of social activities: “[French army officers] Humblot and Demeur Lenaere in for tea. Louise had the flu so we had tea in her room” (February 16, 1920).

I was struck when re-reading these pages how cavalier Sylvia seemed to be, even after caring for close family members who became seriously ill and died, and her own lengthy episode of illness. I would have expected a woman with nursing training to have more to say about the major health event of her lifetime, but she was a young and somewhat light-hearted woman for most of the two years covered in this diary. Perhaps she simply felt the lack of vulnerability that many young people seem to experience. She was in Aintab during a brief but momentous conflict, and in her diary and letters she dismissed any sense of danger. Her unflappable reaction to being under fire gained her recognition from the French government, which awarded her the Croix de Guerre for her cool-headed evacuation of French soldiers during a skirmish.[8]

While these notes reflect the views of one young woman, her thoughts and activities may have been routine for many of our ancestors as they dealt with the devastating influenza pandemic of a century ago. Many of them continued their usual activities, visiting family and friends, attending public social events, and even traveling internationally, despite intimate knowledge and experience of illness and death. It is concerning to see similar behavior today, as people ignore medical advice. Such actions likely prolonged the 1919 pandemic just as the desire to engage in social activities while avoiding wearing a mask is delaying our ability to control the spread of COVID today.

Kathleen Sheldon has been a Research Affiliate at the Center for the Study of Women for over thirty years. Her most recent publications are African Women: Early History to the 21st Century (2017) and Historical Dictionary of Women in Sub-Saharan Africa (2nd edition, 2016), which was a co-winner of the Conover-Porter prize for an outstanding reference work, presented by the Africana Librarians Council of the African Studies Association. She is a recipient of a 2019-2020 Tillie Olsen Grant.

[1] William D. Wintz, Nitro: The World War I Boom Town (South Charleston, WV: Jalamap, 1985), 45–46.

[2] George was most likely her brother-in-law George Buckland, who was married to her sister Cornelia.

[3] Likely Harry Phelps Eno and Mary O’Meara Eno and their 7-year-old son Chester, who all survived the flu; the Enos were a prominent family in Simsbury.

[4] Alexander Navarro and Howard Markel, “Politics, Pushback, and Pandemics: Challenges to Public Health Orders in the 1918 Influenza Pandemic,” American Journal of Public Health 111, no. 3 (2021): 416–422. Navarro and Markel discuss theater closures in the fall of 1918, among other actions that should have directly impacted Sylvia Eddy’s activities.

[5] The USS Leviathan was a troopship that had suffered a terrible loss to influenza just a few months earlier. As it sailed from the US to Europe in September 1918, over 2,000 of the 9,000 soldiers on board fell ill with the flu, and 91 died. See Henry A. May, “Influenza on a Troopship,” in History of the USS Leviathan (1919), reprinted in World War I and America: Told by the Americans Who Lived It (Library of America, 2017), 593–597.

[6] George L. Richards, ed., The Medical Work of the Near East Relief: A Review of Its Accomplishments in 1919–1920 (New York: Near East Relief, 1923), 6. Mentions his presence on the USS Leviathan.

[7] Grace Blakeman Eddy was married to Sylvia’s brother Sherman; Grace Eddy’s obituary does not mention a cause of death; see New-Church Messenger (April 23, 1919).

[8] Further details in Kathleen Sheldon, “‘No more cookies or cake now, “C’est la guerre”’: An American Nurse in Turkey, 1919 to 1920,” Social Sciences and Missions 23, no. 1 (2010): 94–123.