Learning to Read the Room: A Call to Review Feminist Research Methods Post FOSTA-SESTA

By Elizabeth Dayton

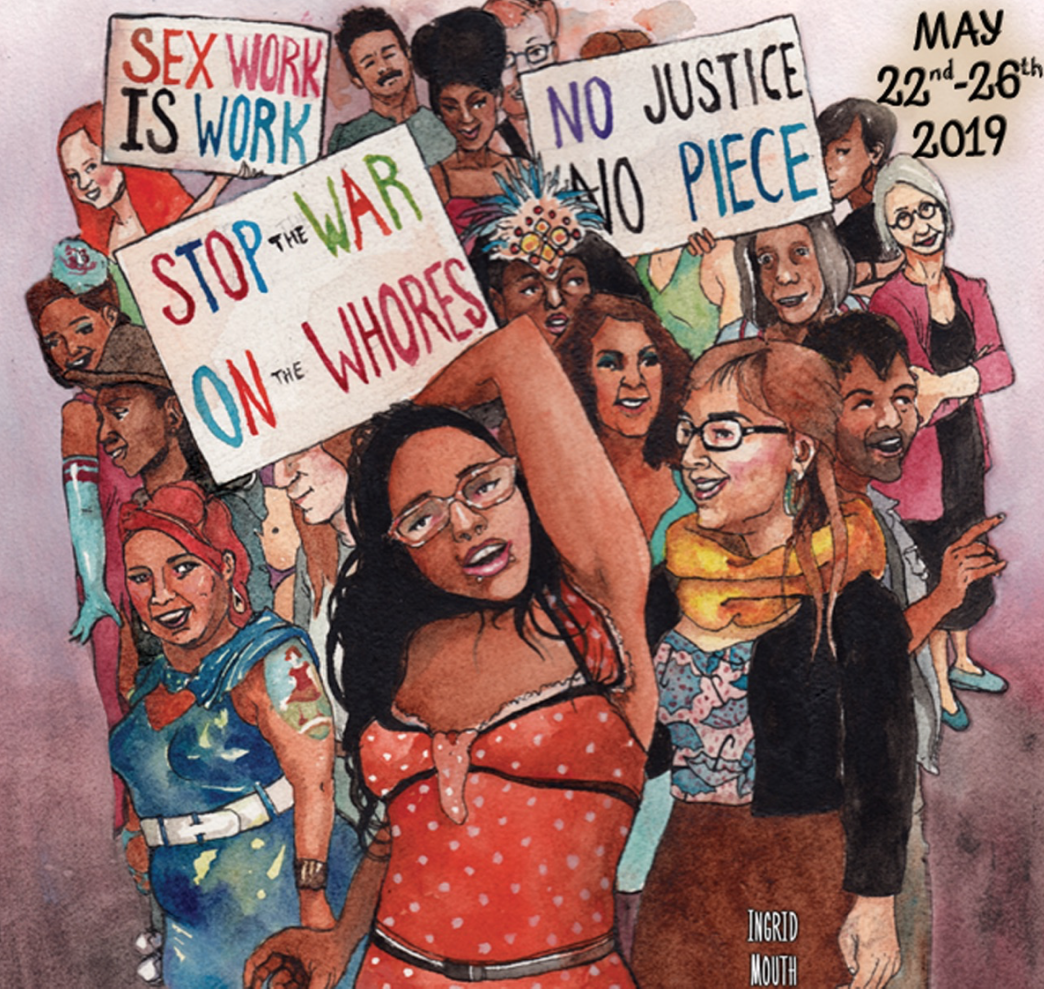

“Sex Worker Film and Arts Festival Poster Image”

Credit: Ingrid Mouth and http://www.sexworkerfest.com/.

In May of 2019, current and former sex workers gathered among peers, friends, and allies for the biennial Sex Worker Film and Arts Festival in San Francisco. Founded in 1999 by Carol Leigh, the earliest festivals focused on showcasing films and video work created by Bay Area sex workers. Over the years, Sex Worker Fest has expanded into a multiple-day festival with events spanning from film and visual art screenings of sex worker artists, to performances, workshops, fashion shows, as well as political organizing events.1 Despite the celebratory nature of the festival, last year’s events bore a somber weight of sorrow and community loss. Attendees gathered for the opening night festivities for an evening of film screenings in memory of beloved community member Laura McElroy. McElroy had been a treasured long-time community advocate for QTPOC sex workers who was lost earlier in the year. Tearful attendees and organizers arranged a visual memorial to mourn the grave community loss and noted the festival would not be the same.

In addition to the very personal loss of McElroy, last year’s gathering also felt the burden of increasing criminalization of the sex industry through the passage of the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking and Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (FOSTA-SESTA) in April 2018. FOSTA-SESTA follows the legacy of existing anti-trafficking policies (Trafficking Victims Protection Act), but extends the criminalization of purchasing sexual services to online platforms by amending Section 230 of Telecommunications Act of 1996. Previously, under Section 230, web hosting platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, or “any interactive computer service,” were not held legally responsible for published content of third-party-users as a proponent of ensuring free speech online.2 FOSTA-SESTA amends Section 230 to “clarify” it “was never intended to provide legal protection to websites that unlawfully promote and facilitate prostitution and websites that facilitate traffickers in advertising the sale of unlawful sex acts with sex trafficking victims.”3

The effects of FOSTA-SESTA legislation are horrific for sex workers and victims of trafficking alike. Immediately after the legislation was signed, the popular advertising site backpage.com was shut down for the felony facilitation of trafficking, despite court-held evidence the website worked with law enforcement to prevent human trafficking and use of the site by minors.4 Many other web platforms utilized by sex workers for advertising, screening practices, and basic safety were shut down (Craigslist Personals, Bay Area City Vibes and entire Reddit sub-boards), and/or their terms of service were amended to prohibit “explicit” or “Not Safe For Work” (NSFW) content (Facebook, Patreon, Tumblr, Google). The economic distress generated from the loss of these online resources increases the likelihood that sex workers will engage in more risky work behaviors (unprotected sex, seeing dangerous clients, working with pimps, returning to street/bar work) making them more vulnerable to exploitation, trafficking, violence, and death.5 As a result of FOSTA-SESTA, the number of reported deaths of sex working community members has drastically increased and makes victims of trafficking harder to identify, reach, and assist.6

Included in the opening-night lineup of the 2019 Sex Worker Festival, the short film Is friendship legal under SESTA? FOSTA? theorizes the impact of FOSTA-SESTA not only on working conditions within the criminalized sexual economy, but also in how the legislation makes it difficult for sex workers to foster platonic and romantic relationships with other people more broadly (both within and outside of the sex industry). The short film takes the audience along on a trip amongst sex-working friends Ms. Zoe Cat, Salty Brine, and Juba Kalamka, as they negotiate which parts of their activities in the sexual economy are legal and which are not. Is getting paid for sexual services legal? What if those sexual services are in front of a camera? If one party made money from illegal sexual services and uses that money to pay for a group activity, are they all committing a crime? The short film draws attention to how FOSTA-SESTA has further criminalized community formation among sex workers by making quotidian acts such as sharing income or discussing work-safety practices considered felony trafficking in the eyes of the legal system.

As more and more academic work is being produced regarding sex work and the sex industry, researchers must be even more aware of the increased precarity that their subjects and collaborators are working under.7 FOSTA-SESTA’s increased criminalization of the sex industry has made it dangerous for sex workers to even speak to other sex workers, let alone researchers.8 Institutional Review Boards are instituted within the academy to protect subjects, but many of their parameters suggest the bare minimum of protections and many sex workers are, quite frankly, tired of working with researchers.9 Ethical research is more than what questions you ask and/or to whom you ask the questions. It is reflecting on if the act of asking itself is an ethical one, and I would say, no. Currently the heralded feminist research praxis of interviews within the sex-worker community cannot be applied universally or without critique and additional safety precautions. Asking sex workers, who are not already speaking due to existing stigmas and criminalization of their work in the sex industry, to take on additional risk by participating in research post-FOSTA-SESTA is not ethical research praxis.

However, this does not absolve researchers from tackling issues relevant to the sex industry. Rather, it obliges them to listen and work with sex workers who are already speaking publicly. What are they saying? How can we, as researchers, amplify pre-existing contributions from sex workers to academic and legislative discourses of the sex industry, and allow these narratives to direct future research projects? As a researcher whose work involves the sex industry, and who works from a feminist sex-workers’ rights perspective, I urge fellow researchers to reexamine their methodologies to accommodate the changing needs and heightened risks of their sex-working partners and subjects.

Elizabeth Dayton is a PhD student in Gender Studies analyzing dominant narratives of sex work in mainstream media and how these narratives often conflict with how many sex workers understand their own lives, experiences, and relationships to their work. She received a CSW Spring Travel grant in 2019.

- “About SexWorkerFest,” San Francisco Bay Area Sex Worker Film and Arts Festival, http://www.sexworkerfest.com/about.html.

- Feb. 8, 1996, [S.652] Telecommunications Act of 1996. 47 USC 609 note

- “Congressional Record Proceedings and Debates for the 115th Congress, Second Session,” 164, No. 47 (March 19, 2018), https://www.congress.gov/congressional-record/2018/03/19.

- Brown, Elizabeth Nolan, “Secret Memos Show the Government Has Been Lying About Backpage All Along,” Reason, August 26th, 2019, https://reason.com/2019/08/26/secret-memos-show-the-government-has-been-lying-about-backpage/.

- Weitzer, Ronald, “Sociology of Sex Work,” The Annual Review of Sociology 35 (2009): 213-234.

- “2018 Memorial List,” december17.org, accessed December 20, 2018.

- D’Adamo, Kate, “Sex (Work) in the Classroom: How Academia Can Support the Sex Worker Rights Movement,” in Challenging Perspectives on Street-Based Sex Work, ed. Katie Hail-Jares, Corey S. Shdaimah, and Chrysanthi S. Leon (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017), 194-215.

- Is friendship legal under SESTA? FOSTA?

- Field Notes from Desiree Alliance 2016, San Francisco Film and Arts Festival 2017 and 2019.

Comments are closed.