Telling a Historian’s Story

When I lived in Beira, Mozambique, for two years in the early 1980s while pursuing my dissertation research, I kept a daily journal about my experiences. My husband, a pediatrician, worked for the Ministry of Health and our toddler daughter was also with us and attended a local daycare program. I recorded the details of daily life as an increasingly deadly war developed in Mozambique and we confronted food shortages and other obstacles. I also noted my stumbling beginnings as a new historian, as I discovered the lack of archives in the city where we lived and learned working women’s history by collecting oral testimony from nurses, market vendors, and women in cashew and garment factories.

Some years ago, I turned that journal into a memoir of those years in Beira, though it remains unpublished while I have collected a file full of rejections. Publishers who have read my proposal and the manuscript have all liked it but have confessed that they do not know how to market it – it has a bit too much history to be sold as a personal memoir, and far too much personal experience to market it as a history text. In any case, I finished my dissertation and published a history of women in Mozambique; the memoir was never intended to replace that history1. It seems that there are particular, stereotypical ideas of what constitutes the correct kind of “Africa” memoir, and those assumptions influence publishers’ reactions to my story. Such attitudes limit the kinds of stories that are told about Africa, about scholarship, and about women’s lives, and suggest that not all authors’ stories are valued.

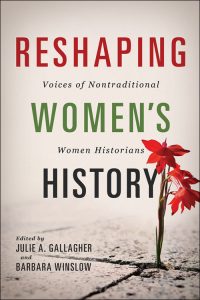

Despite the apparent unpublishable nature of the memoir as a whole, three articles drawn from the manuscript are in print or in the publishing pipeline. Two of those discuss more historical and less personal aspects of my experience in Mozambique2. The third article, the most memoir-like of the three, has just been published in Reshaping Women’s History: Voices of Nontraditional Women Historians3. That collection brought together personal essays by the scholars who have been awarded the Catherine Prelinger Award from the Coordinating Council for Women in History4. All eighteen of the awardees agreed to tell their own stories of an unusual, non-traditional, or circuitous career path to becoming a historian. I have participated on two conference panels with some of the other contributors, and the positive response from audience members to my own story has led me to wonder why the book-length version has been so difficult to publish.

Memoirs by historians have tended to favor particular narrative perspectives. Jeremy Popkin investigated autobiographies written by historians and noted that the main memoirs were by white male scholars. He mentions several by women, but notes that, “The women historians’ memoirs that have appeared up to now [2005] are almost entirely by scholars trained at a time when there were few senior women historians to serve as mentors.5” The best-known autobiographies by women historians are from that cohort, including books by Gerda Lerner, Doris Kearns Goodwin, and Jill Ker Conway.6

Likewise, there are few memoirs by historians who focus on Africa; three of the most notable are by early white male practitioners (Roland Oliver, Jan Vansina, and Philip Curtin) who each claimed they had founded (or helped to found) the field of African history.7 In fact, some of the earliest research, publication, and teaching about African history in the United States was accomplished by scholars at historically black colleges and universities, decades before the work of white historians in the 1950s. Historically, memoirs and autobiographies by non-Africans who lived and worked in Africa were often by missionaries, including many women, who wrote about their quest to spread Christianity. More recent memoirs are commonly by anthropologists and aid workers, particularly many by Peace Corps volunteers. For those groups, writing up their experiences while living and researching in Africa and elsewhere is a widely accepted practice and there is an extensive bibliography of such works.8

As I wanted to discover what kind of Africa memoir was publishable, I read many books by Americans who had lived or worked in Africa. I noticed an accepted meta-story: a young American, usually white and privileged, goes off to Africa knowing little about her destination but desiring to learn and to help. A noticeable number traveled in order to escape an unhappy relationship in the U.S. Our traveler lives as an individual in a remote rural village where she gains great insight into “Life.” My story followed nearly the opposite trajectory. I had prepared to go to Mozambique with years of graduate study and research in archives in Portugal. I chose Mozambique because I supported their socialist policies which included positive support for advancing the status of women. My husband and I viewed our work there as contributing to an international socialist movement. We lived in a city, the second-largest in Mozambique, and were restricted from even visiting rural areas due to the developing conflict. Our daughter attended local daycare centers, and my experience as a mother pursuing a research agenda was an important part of my experience. I know that some aspects of my story are shared by other women historians who have done research in Africa, but as far as I know, no memoirs have been published by those colleagues.

Since I returned to the United States over thirty years ago, I have recounted many stories about our time in Mozambique and have often been told that I should write a book. But now that I have written the book, publishers are wary. One agent who I approached responded that no one in the U.S. cared about what happened in Mozambique, a sorry comment on many levels. Nonetheless, I have been buoyed by the interest of the attendees when I have participated in conference roundtables related to Reshaping Women’s History, and I believe there is an audience for my story. It may not provide the usual outline of a naïve traveler who lands in a rural African village and writes about her encounter with a community presented as remote and exotic. I still trust that there is an audience for a book about becoming a feminist historian while learning about African women’s history. I hope it will eventually get published, but in the meantime, the chapters now in print bear witness to my story.

Kathleen Sheldon has been a Research Affiliate at the Center for the Study of Women for over thirty years. Her most recent publications are African Women: Early History to the 21st Century (2017) and Historical Dictionary of Women in Sub-Saharan Africa (2nd edition, 2016), which was a co-winner of the Conover-Porter prize for an outstanding reference work, presented by the Africana Librarians Council of the African Studies Association. She received Tillie Olsen grants in 2017 and 2018 to support her participation on conference panels related to Reshaping Women’s History.

- Pounders of Grain: A History of Women, Work, and Politics in Mozambique (Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann, 2002).

- “Creating an Archive of Working Women’s Oral Histories in Beira, Mozambique,” in Contesting Archives: Finding Women in the Sources, ed. Nupur Chaudhuri, Sherry J. Katz and Mary Elizabeth Perry, 192-210 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010); “‘Down with Bridewealth!’ The Organization of Mozambican Women Debates Women’s Issues,” in Feminist Readings of Political Communication in Africa, ed., Sharon Omotoso (Springer, forthcoming 2019).

- “Finding My Way in African Women’s History,” in Reshaping Women’s History: Voices of Nontraditional Women Historians, ed., Julie A. Gallagher and Barbara Winslow (University of Illinois Press, 2018; https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/catalog/48dte6fd9780252042003.html).

- More information on the award and the recipients is at https://theccwh.org/ccwh-awards/catherine-prelinger-award/.

- Jeremy D. Popkin, History, Historians, and Autobiography (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005); quote on women historians, 147.

- Gerda Lerner, Fireweed: A Political Autobiography (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002); Doris Kearns Goodwin, Wait Till Next Year: A Memoir (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1997); Jill Ker Conway, The Road from Coorain (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989).

- Roland Oliver, Realms of Gold: Pioneering in African History (New York: Routledge, 1997), is the only one mentioned in Popkin, History, Historians, and Autobiography, 174-175; Philip D. Curtin, On the Fringes of History: A Memoir (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2005); Jan Vansina, Living with Africa (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994); see also Merrick Posnansky, Africa and Archaeology: Empowering an Expatriate Life (London: I. B. Tauris, 2009).

- Anthropologists have a book series dedicated to the topic, “Writing Lives: Ethnographic Narratives,” now housed at Routledge, https://www.routledge.com/Writing-Lives-Ethnographic-Narratives/book-series/WLEN. Search “Peace Corps memoirs” to find various lists; one is “Sharing Experiences with the World: Memoirs of Returned Peace Corps Volunteers,” at the Peace Corps Community Archive https://blogs.library.american.edu/pcca/sharing-experiences-with-the-world-memoirs-of-returned-peace-corps-volunteers/.