Women’s Portrayals of Friendship in Renaissance Italy

By Adriana Guarro

Why Female Friendship?

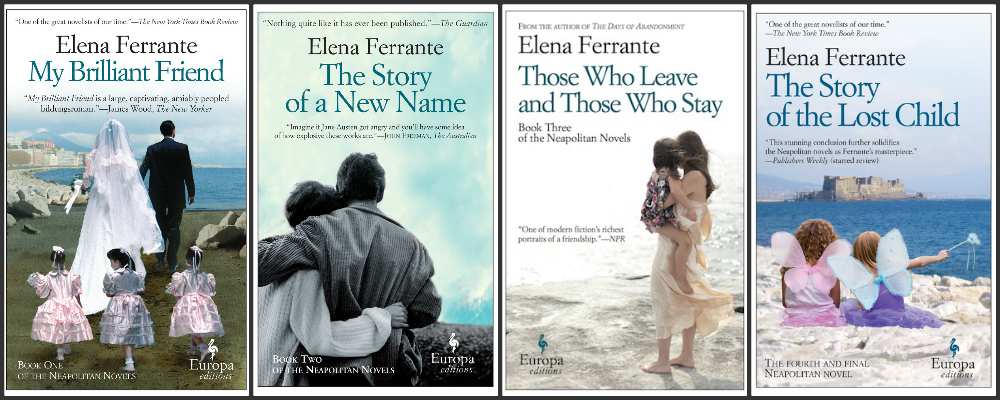

I spent the winter break of my first year of graduate school at UCLA in my father’s hometown in central Italy reading the Neapolitan novels, a four-novel series of books penned by the pseudonymous Italian writer Elena Ferrante which set off worldwide “Ferrante fever.”1 The series is set in postwar Naples and tells the story of the lifelong friendship between two women, Elena and Lila, along with the hardships and successes that shape both of their lives.

Like many readers of the quartet, I was captivated by Ferrante’s literary world which places female friendship as the most important bond in a woman’s life, even superseding relationships between mothers and daughters, husbands and wives, and sisters. Moreover, there was something in her nuanced and raw portrayal of the two women’s bond that resonated with me. Indeed, Ferrante does not present friendship as an idyllic relationship that only brings happiness and joy. She instead represents its complex depth, expressing how friendship can cause love and happiness, but also how it can be the cause of pain and anguish, and can inspire competition. It was after reading these four novels that I knew that I wanted to pursue the topic of women’s friendships further, but in the context of my own field of interest—Renaissance Italy.

Today, women’s friendships and networks are often celebrated in the media as empowering forces that remain integral to women’s personal development. Like Ferrante’s novels, many popular TV series including Big Little Lies (2017), The Handmaid’s Tale (2017), and Insecure (2016) have treated the bonds between women as their primary subject. However, in Renaissance Italy, where classical notions of friendship held strong, many saw friendship between women as an impossibility. To most Renaissance thinkers, who were primarily men and influenced by classical texts, friendship was idealized as a purely male experience. This explains why most of the language depicting friendship in theories, treatises, and even fictional texts from the period is male-oriented.

Even though male notions of friendship dominated the conversation, we still find many depictions of female friendship in Italian Renaissance texts. How then, was female friendship understood in Renaissance Italy? How was it depicted? And did its representation bear any resemblance to its male counterpart, or was it conceptualized in a completely different manner? My doctoral research stems from these questions. In an attempt to answer them, I turn to literary texts written by sixteenth-century Italian women across three different genres (lyric poetry, epic poetry, and epistolary writing) to examine women’s representation of friendship and whether they aligned (or not) with male considerations of friendship.

Female Friendship in Renaissance Italy and My Research Thus Far

Left: a letter from Margherita Sarrocchi to Galileo Galilei. Right: a portrait of Margherita Sarrocchi.

While important scholarly work has been done on the impact of female friendship on modern Italian literature, especially with respect to the 1970s Italian feminist movement, the topic has hardly been broached with respect to the Renaissance. In fact, female friendship in the Italian Renaissance has been largely relegated to footnotes or is dismissed in broad, overarching statements, such as Ulrich Langer’s claim that “exemplary female friendship in French and Italian literature before the seventeenth century and in moral philosophy is highly infrequent.”2 Evidently, Langer’s claim is flawed. Though it is true that examples of male friendship in Renaissance Italian literature are more prevalent, we need to recognize that this was only because the male tradition was dominant. When we look more closely, we find numerous depictions of female friendship in many popular Renaissance genres that have yet to be examined. I argue that from these representations we may gain a better understanding of female friendship as a historical reality in early modern Italy.

Thanks to the generous support of the Center for the Study of Women at UCLA, I have been able to further my research on the first chapter of my dissertation, which examines the representation of female friendship in an epic poem authored by Margherita Sarrocchi (1560‑1617). Sarrocchi was an extraordinary woman whose life was not typical for most women living in early modern Italy. For one, she received a thorough education in the humanities and sciences, a privilege that at the time was primarily reserved for men. Secondly, she was a sociable woman; she organized intellectual gatherings at her home, belonged to a number of well-known literary and scientific academies, and she maintained networks that connected her to renowned individuals like Galileo Galilei (1564‑1642) and important members of the Papacy. And thirdly, she excelled in both the sciences and humanities. She published essays on mathematical theorems, a commentary on Petrarchan poetry, a translation of ancient Greek lyric poetry, and a number of her own lyric poems, which were featured in well-known anthologies. But, undoubtedly, Sarrocchi’s biggest literary feat was her epic poem, the Scanderbeide, to which Sarrocchi dedicated most of her life. A partial, unfinished version of the poem was published first in 1606, followed by a posthumous final edition in 1623. The English translation of the title, Scanderbeide, is “a poem on Scanderbeg,” just as the Iliade (Italian for Iliad) means a poem on Ilium, or Troy. The Scanderbeide is a historical heroic epic poem set during the mid-fifteenth century (from about 1443 to 1468) that tells the story of Gjergj Kastriori or Scanderbeg (1405‑1468), an Albanian hero, and the successful rebellion he led against the Ottomans in what is today Albania and Macedonia.

Many classical and Italian Renaissance epic poems, including Homer’s Iliad (IX-VIII century BC), Virgil’s Aeneid (19 BC), Statius’s Thebaid (80-92 AD), Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso (1516-1531), and Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata (1581), highlight the importance of friendship, especially between men. Sarrocchi’s poem is significant as it is one of the first epic poems to strongly feature female friendship. Her characterization of the friendship between two women warriors named Silveria and Rosmonda does not simply mirror previous classical and Renaissance models, but introduces aspects that are entirely new. For example, Sarrocchi repurposes the qualities of sameness, mutual affection, and reciprocity, which were typically found in descriptions of male bonds, to depict Silveria and Rosmonda’s friendship. Sarrocchi also rewrites Ariosto and Tasso’s representations of female friendship to show that women’s bonds do not center around a male character nor are they naturally ripe with strife and envy. Both of these elements had never been seen in an epic poem before. By revising these traditional elements and depicting a female bond as the most important relationship in her poem, Sarrocchi presents us with a new way of thinking about epic friendship, one that grounds it as a female experience.

Adriana Guarro is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Italian at UCLA. She received a CSW Travel Grant in Fall, 2017.

- As reported in a December 2016 New York Times article, Ferrante’s novels sold nearly two million copies in North America and more than a million copies in Italy, and had climbed to the top of the best-seller lists in France, Germany, and Britain. Additionally, HBO has recently bought the rights to all four volumes of the series and will produce a TV series on the tetralogy, to be released as early as 2019. See Alexandra Alter. “‘Ferrante Fever’ Continues to Spread,” New York Times, December 16, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/07/arts/ferrante-fever-continues-to-spread.html; John Koblin, “Elena Ferrante Series Coming to HBO,” New York Times, March, 30, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/30/business/media/elena-ferrante-series-coming-to-hbo.html.

- Ulrich Langer, Perfect Friendship: Studies in Literature and Moral Philosophy from Boccaccio to Corneille, (Geneva: Librarie Droz, 1994), 117.