Imagining Utopias: Toward Latinx Feminist Thought

What does it mean to disappear—from the pages of history, from your own humanity, from systems of oppression? For people of Latin American descent throughout the Americas, disappearance takes many forms: the physical and cultural genocide wrought by European colonization; murders and sexual assaults resulting from military coups, environmental pollutants, authoritarian regimes, lack of quality healthcare (including abortion) access, drug cartels, poverty, and civil wars; mass incarceration; forced migration; deportation; and gentrification; among many others. While these examples highlight various mechanisms for the physical disappearance of Latinx bodies, social movement spaces remain a site for the disappearance of Latinx feminist action. Organizations such as California Latinas for Reproductive Justice (CLRJ) enact the principles of intersectionality by demonstrating the necessity to view Latinxs’ reproductive lives at the intersections of multiple identities, contexts, and inequalities, and in the process act as bridges between racial, feminist, immigrant, economic, and other social movements. Yet, their contributions are at times eclipsed by those of mainstream (read: white) reproductive rights activists who receive more media attention, and funding, and who co-opt the reproductive justice lens without crediting or collaborating with reproductive justice organizations.

In academia, too, Latinx experience disappearance of their ways of knowing. Communities of color, women, and queer people have long been misrepresented in policy and academia, and those misrepresentations have been used to justify the very forms of interpersonal and institutionalized violence described above. These communities challenge normative assumptions of knowledge production based on the colonialist perspectives through which U.S. institutions of higher education were founded. Yet, ethnic studies, gender studies, and queer studies generally garner less funding than ‘traditional’ disciplines; ethnic studies in particular are under constant threat of eradication; and scholars in these fields as well as scholars on the margin of traditional disciplines face significant lower rates of tenured positions compared to white men, experience heightened anxiety, depression, and exhaustion (Gutiérrez y Muhs et al. 2012), and are often forced to defend the quality and rigor of their work via institutional channels that maintain white-centered values toward knowledge production alive and well. Furthermore, while Latinx queer and straight feminists have contributed their experiences and perspectives towards imagining and enacting possibilities for liberation, their stories are still marginalized due to claims that they lack ‘objectivity.’ Amidst these intersecting manifestations of oppressions, Latinx feminist practice and theories have long engaged in disappearing acts of their own: escaping toxic spaces as a radical form of self-care and taking part in intersectional social justice projects to erase oppressive systems that exert violence against them and their communities, planting seeds of hope to imagine utopian futures beyond our own.

Drawing on three years of ethnographic observations with CLRJ as a launching point, my dissertation, Latinx Feminist Thought: Visions of Reproductive Justice, Anti-Colonization, and Utopias, captures a dialectic of disappearance in the perspectives and experiences of Latinx feminists within and outside of the academy as we collectively resist our systemic disappearance. The work of Latinx feminists shows that to create better worlds, we must first imagine them (Kelley 2003). By charting the contributions of CLRJ in tackling current reproductive oppressions, I center how Latinx feminists define and redefine utopia on their own terms.

In 1990, Patricia Hill Collins brilliantly captured many of the complexities of Black women’s experiences and ideas as a vehicle for empowerment and knowledge production in Black Feminist Thought, but there exists no contemporary parallel vision for Latinxs. Broadly, women of color feminisms in movements for social justice reflect a longstanding mosaic of visions, struggles, debates, and ideas, as marginalized communities continuously imagine possibilities for liberation. Recent Afrofuturist work (Butler 2007; Nelson 2002) draws on the subjectivities of Black women to imagine social worlds beyond the existing confines of racial, gender, sexual, class, globalizing, and nation-based inequalities. Similarly, Chicanx feminist thought demonstrates that intersectionality is not simply a theory or a concept in the academy; it is generated in the quotidian experiences of women of Latin Americna origin (Anzaldúa 1987; Moraga and Anzaldúa 1981). Latinx feminisms draw on the spirituality of indigenous and ancestral ways of knowing as a catalyst for decolonizing knowledge and systems of inequalities (Facio and Lara 2014). However, little work has coupled these strains of feminist thought to interrogate how a theory of disappearance can not only elucidate the connections across incredibly diverse Latinx communities, but also how such coupling enables opportunities to expand an inclusive feminist vision of justice and liberation via alternate futures.

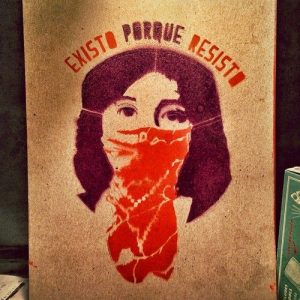

I find that the work of CLRJ—focused equally on fighting for the right to parent, not parent, and to parent in healthy and safe environments—along with the past and current work of Latinx feminists within and outside of academia demonstrates that Latinx feminist thought centers on negotiating a politics of disappearance. The politics of disappearance refers to the linked mechanisms that physically, politically, and academically disappear Latinx communities, and the various strategies Latinx feminists engage in to disappear from and to disappear systems of oppression. Disappearance serves multiple functions: the existence of Latinx feminisms is evidence of how disappearing can be an active stance and a means to escape and/or fight against the traumas of systemic inequalities. In this context the work of CLRJ and the ideas, songs, and experiences of Latinx feminists across what we now call the Americas highlight five distinguishing features of Latinx feminisms: 1) an active refusal to be disappeared via activisms and recovering memories and histories; 2) the reclamation of negative representations into images of Latinx feminist empowerment; 3) the provision of solace, healing, and hope; 4) intellectual ways of knowing in the academy rooted in lived experiences; and 5) fluid and relational analyses that amplify both similarities and differences within and across Latinx communities.

It is in the moments when Latinx feminists experience the dialectical relationship between the violence of being disappeared and the power of choosing to disappear, that possibilities for a new type of consciousness can emerge. This transcending consciousness is not only capable of withstanding oppression, but is necessary for imagining and travelling to future worlds where all communities can experience self-determination, joy, and justice outside of the confines of colonization. Inspired by indigenous ways of knowing (Brown and Strega 2005), queer utopian theories of fluidity and non-linearity, (Muñoz 2009), and borderlands theories that challenge linear notions of time, this time-travelling transcending consciousness reflects the lens of Latinx feminisms at the intersections of being disappeared and disappearing, and is, I argue, a form of knowing imperative for utopias. A transcending, Latinx feminist consciousness requires the following: 1) a recognition that western uses of binaries and time have justified violence against marginalized communities; 2) the use of compassion and love as radical sensibilities; 3) the active imagining of utopias as resistance; 4) the use of storytelling in constructing knowledge; 5) a commitment to coalition-building as a means of constructing and deconstructing knowledge and accountability; 6) the centering of indigenous and queer perspectives as agents of knowledge and liberation; and 7) working with activists outside of the academy to decolonization the academy.

In charting a pan-ethnoracial Latinx feminist framework, I highlight the strength, resiliency, compassion, and brilliance of Latinx feminists across the Americas, demonstrating that visions of liberation and utopia must center the experiences and ways of knowing of Latinx feminists.

Rocío R. García is pursuing a Ph.D. in Sociology at UCLA. She was awarded a CSW Travel Grant to present her research at the Intersectional Inquiries Conference at the University of Notre Dame in 2017.

References

Anzaldúa, G. 1987. Borderlands La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books.

Butler, O. 2007. Fledgling. New York, NY: Grand Central Publishing.

Collins, P.H. 1990. Black Feminist Thought. New York: Routledge.

Facio, E. and I. Lara. 2014. Fleshing the Spirit: Spirituality and Activism in Chicana, Latina, and Indigenous Women’s Lives. University of Arizona Press.

Kelley, Robin D.G.. 2003. Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. Boston: Beacon Press.

Moraga, C. and G. Anzaldúa (eds.). 1981. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings of Radical Women of Color. Kitchen Table/Women of Color Press.

Nelson, A. (ed). 2002. Afrofuturism. A Special Issue of Social Context. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Comments are closed.