Being and Becoming a Midwife: Pedagogical Practices, Objects, and Gendered Knowledge in Eighteenth Century France

by Scottie Buehler, CPM, MA

In eighteenth-century Europe male obstetrical practitioners began regularly attending uncomplicated childbirths, eventually challenging midwives as the primary care providers and obstetrical experts. While midwives argued that their female bodies and experiences gave them true obstetrical knowledge, male practitioners disagreed, instead emphasizing anatomical and medical learning. Various midwifery training courses, ranging from small rural classes to the large institutional training at the Hôtel-Dieu of Paris, functioned as sites that created and gendered obstetrical knowledge.

In my research, I use published books, student notes, images, and material objects such as instruments and obstetrical mannequins, to show how knowledge was transmitted and gendered in classrooms, in training sessions, through books and images, and via hands-on training. By incorporating objects and practices into my study, I bring the lived experiences of people traditionally denied access to publication to the forefront. To better understand eighteenth century French midwifery education I ask: How did different regional differences shape specific pedagogical practices? What types of knowing were privileged and why? Were these ways of knowing symbiotic or competing, when and why? What role did gender play in the privileging of certain types of knowledge over others? And finally, what was at stake in debates around the contested use of objects, such as mannequins, instruments, and images, for training midwives and accoucheurs (man-midwives)?

I organize my dissertation around five specific midwife training courses. No single narrative could capture the complexity and diversity of early modern midwifery training, but these five sites provide sensitivity to geographic location. They illuminate the multifaceted relations between educational theory, state interest, religious and moral beliefs, and pedagogical practices within specific locales. I contextualize these detailed investigations of pedagogical practices within the larger concern of state administrators with population statistics, debates concerning rural midwives, and controversies over the epistemological legitimacy of objects in pedagogy. This move between the specifics of the pedagogical practices of these sites and wider state and institutional interests in educating midwives engages with questions of power and agency. The state created policies and set the tone of the discourse concerning midwifery education, but within the classroom many interests and identities merged to create the practices of individuals.

All areas of health and illness were increasingly medicalized in the eighteenth century but the female reproductive body is a particularly striking example because it was an area of health previously left, mostly, outside the control of the medical establishment. Such questions as the normal length of pregnancy became contentious topics worthy of debate at the highest levels of intellectual society.[1] Historian Lisa Forman Cody even argues that the reproductive body and the political body became tied together in eighteenth century Britain. This linkage brought reproduction into the public light and under the domain of masculine knowledge and institutions.[2]

The debates around midwifery education reveal how the construction of women’s bodies (and their health) as boundary markers between rationality and irrationality, between nature and technology, and between progress and ignorance caused tension concerning gender, epistemology, the relationship of government to its people, and even the definition(s) of health.[3] These tensions are especially heightened in discourse about provincial midwives. The ignorance of the provincial midwife was an assumption so ubiquitous and unquestioned that the phrase “une sage-femme du campagne” (a country midwife) was nearly always accompanied by the noun “l’impéritie” (incompetence) in newspapers, as well as in obstetrical texts written by both men and women.[4] The trope of the ignorant and unskilled midwife was not exclusive to France, but developed all across Europe. In England, the solution to the “problem” of the incompetent midwife was not education, but the forming of a new, more educated professional, the man-midwife. Yet, in France, there is little evidence of a public discourse debating whether or not midwives should be educated. Instead, the philosophes and medical professionals who participated in these discussions faced a dilemma: how to bring rationality and progress to a group of people who embody irrationality and ignorance?

The history of midwifery has always been told through the lens of sex and gender, of men triumphing over women. Even accounts that have attempted to complicate the simple male/female dichotomy by looking at medical professionalization and medicalization have ended up reinforcing it by equating professionalization with masculinization. For instance, according to historian of science Londa Schiebinger, in the second half of the 18th century, ideas of sex difference began to change, and anatomists, such as Jakob Ackermann, sought to discover the essential (read: biological) differences of the sexes.[5] Shiebinger takes a cultural constructivist approach to gender, interrogating how early modern European society represented the categories of “male” and “female” and assigned traits and behaviors to them accordingly. But she, and constructivist ideas of gender more generally, fails to fundamentally question the categories of “male” and “female.”[6]

Instead, I employ the definition of gender supplied by Joan Scott: gender, Scott writes, is “a historically and cultural specific attempt to resolve the dilemma of sexual difference, to assign fixed meaning to that which ultimately cannot be fixed.”[7] Individuals do not have fully formed, coherent notions of gendered selves as Liberal philosophy argues. The self turns to objects and people outside itself for recognition, objects and people which are also subjected to the individual’s beliefs about gender and as well as their own. It is through such actions as group membership that individuals learn to identify themselves as “male” or “female.”[8] This approach to gender allows me to embrace contradictions in my historical subjects, not erase those contradictions to create autonomous, coherent individuals. Moreover, it recognizes the role of communities and objects in shaping gender identity.

Madame du Coudray, Abrégé du L’art de accouchements (1777). This is du Coudray’s portrait placed across from the title page of her book.

Midwifery mannequins embody many of the eighteenth century controversies over gender and knowledge. In addition to replicating gendered knowledge about anatomy, physiology, and childbirth, they were also contested objects. For centuries physicians and surgeons employed anatomical models to freeze the body in a specific moment of time.[9] Madame du Coudray dominated the medical world of childbirth in the second half of the eighteenth century France, at least in part due to her invention of a midwifery mannequin. Within a decade of earning her midwifery certification in 1740 in Paris, du Coudray set herself the mission of educating rural midwives. To support this pedagogical project she invented the mannequin, or “machine” as she named it, sometime in the early 1750s and wrote a textbook, Abrégé de L’art des Accouchements (1759). Upon publication of her textbook the king of France, Louis XV, awarded her a brevet, and a 700 livres gratuity, to travel the countryside teaching midwifery courses to female and male practitioners. Du Coudray used a combination of text, image (26 color plates were later added to her textbook), and the mannequin to instruct her students in her course. While we cannot fully understand du Coudray’s pedagogical project solely through her mannequin, a brief investigation reveals that the debates surrounding educating midwives did not fall easily along gendered or professional lines.

On December 1, 1756, Madame du Coudray received an official approbation from the College of Surgery for her obstetrical mannequin. The record of the College reads,

“Messieurs Verdier and Lavret were nominated by the College to examine a machine invented by Madame du Coudray, Mistress Midwife, received in Paris, established in Clermont in Auvergen, in order to demonstrate the practice of Childbirth, having made a very advantageous report, the College judged this Machine worthy of our approbation…”[10]

This was a rare honor—even more so for a woman. In April du Coudray had traveled to Paris to show her machine to La Matinière, the king’s first surgeon, and he had paved the way for her to demonstrate her machine at the College. Mr. Levret, mentioned above as an examiner of the mannequin, was himself a famous accoucheur and inventor of obstetrical instruments.[11] His approval of du Coudray’s mannequin was no small feat for the midwife.

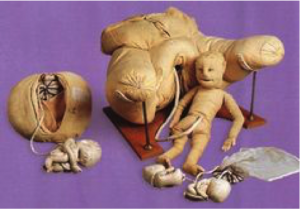

Each piece of du Coudray’s machine was numbered and identified with parchment so that students could test their anatomical knowledge.[12] The parts could be removed, viewed, and put back together, all made to life-sized proportions. The sole (known) surviving mannequin, in a museum in Rouen, is fixed on a wooden base shaped like a birth chair with the legs in stirrups. The whole set needed to be placed on a table in front of a student.[13] Her machine was meant not just to teach, but also to warn and scare. She created replicas of a shriveled umbilical cord and the crushed head of a baby, illustrating the results should a midwife not know the limits of her skills and fail to call in a doctor when needed.[14] The machine also came with accessories that included a set of twins attached to a placenta, and a canvas model of the female reproductive organs. These were not meant for demonstrations but were models to illustrate discussions of anatomy and twin births.[15] The multiple moving parts and multiple functions of the mannequin may be what motivated du Coudray to call it her “machine.”

While such a complex object conveyed high prestige on Madame du Coudray, it also left her vulnerable to criticism. In the second half of the 1770s du Coudray and her educational project came under attack from rival traveling midwifery courses. Jean Le Bas, a surgeon, accoucheur, royal censor, and fellow midwifery educator in Paris, attempted to regain his reputation after a stint in jail for approving a controversial text, by attacking du Coudray’s machine:

“All men, truly in the Art of Delivery, would admit that the best executed mannequin is only a ghost, an enactment, a shadow of truth, capable of giving false ideas to the beginners who, once having their heads filled, would not know to avoid the practice of a bad job on a living subject.”[16]

Musée Flubert et d’histoire de la medicine-Rouen, La “machine” de Madame du Coudray (2004). The only known machine of du Coudray’s that survives. The twins with placenta to the right and the stillborn baby on the left were accessories. The main machine is the large model of a woman’s body with baby.

Le Bas continues by comparing the use of a mannequin to the theatrics of the Opera. His primary attack concerns the divide between the constructed object of the mannequin and a living body. His choice of words such as phantom, simulacrum, and shadow of truth (phantôme, simulacre, ombre du vrai) exposes his belief in the lack of transferability of skills learned on the machine to a woman in labor. For Le Bas, furthermore, these skills create false knowledge that will only cause harm. Instead, he insists that new students practice their skills on living subjects. Though he is not explicit, it seems that he may have less misgivings with experienced practitioners using mannequins as they are less susceptible to the false ideas possibly conveyed by the mannequin.

But du Coudray did not hesitate to respond to these criticisms by marshaling her allies in Paris. Writing in support of du Coudray, an anonymous citizen described the benefits of her work:

“This innocent artifice [the mannequin] succeeded for du Coudray to make the students repeat the maneuvers; these good women were encouraged and succeeded perfectly, to the even greater satisfaction of the Mistress than of Mr. de Tiers who congratulated himself on a very happy success.”[17]

The machine was used to praise du Coudray insofar as it contributed to the education of her students. In praising du Coudray, the mannequin becomes an “innocent artifice” instead of a sinister simulacrum.

Mr. Mouton, a prosecutor and subdelegate for the commune of Saint Menehoud, applauded du Coudray’s mannequin and detailed its benefits for rural students in the Gazette de Santé, a medical newspaper.

“…a public childbirth course, run with the assistance of a machine invented by Madame du Coudray with which numerous students of the countryside have been instructed by their eyes, in that this machine is talking [parlante], so to speak, and by the lessons of demonstrators…This machine appeared very proper to the instruction in general…but also because in the particular case of village women usually little educated, the form of spectacle is more gripping than that of discourse.”[18]

In Mouton’s letter the spectacular aspect of the mannequin is a strength because the students are uneducated. His word choice of “parlante” to describe the mannequin anthropomorphizes it; it is so expressive that it talks and teaches. The word also carries the meaning of “speaking for itself,” thus the mannequin’s instruction to the students needs no explanation or interpretation according to Mouton.

This short vignette concerning the obstetrical machine of Madame du Coudray challenges the traditional historiography of eighteenth century midwifery in which disputes are seen as falling easily along gendered, and their related professional, lines. In this case we see epistemological concerns about objects and pedagogical considerations take prominence over professional/gendered allegiances. However, this does not mean that gender has no place in this story. Du Coudray stepped out of traditional gender roles by gaining such prestige and power as the midwife educator par excellence for all of France, by becoming an author, and by inventing a machine. Yet, she always maintained that midwives should know their place and call in surgeons when appropriate. She too spoke of the ignorance of the country midwife, which, she and Mouton argued, necessitated the visual demonstrations on the mannequin. Furthermore, I think it is significant that Le Bas taught in Paris while du Coudray (and a man-midwife who also advocated for obstetrical mannequins but against du Coudray, Augier du Fot) taught in the provinces. These geographic differences meant that Le Bas’s students were much more likely to be literate than du Coudray’s and this may have shaped their views on the role of mannequins in education.

In my dissertation I further explore this debate around the use of mannequins as well as other controversies such as the role of images in midwifery pedagogy. For now, I am convinced that treating man-midwives or midwives as homogeneous groups with similar concerns and goals erases the myriad of interests, ambitions, and motivations of these individuals.

Scottie Hale Buehler is a midwife turned historian of medicine. After earning her BA in Sociology and Women and Gender Studies from the University of Texas at Austin (2006), she became a Certified Professional Midwife and founded and operated Motherwit Midwifery, a homebirth midwifery practice in Austin, Texas. Her current research focuses on the relationship between knowledge, practice, images, and objects in obstetrical training courses in the second half of the eighteenth century France. In addition to the history of early modern European midwifery, Scottie also researches the history of the body, history of the book, and history of anatomy. She was the recipient of the 2016 Penny Kanner Dissertation Research Fellowship from the Center for the Study of Women.

[1] Lindsay Wilson, Women and Medicine in the French Enlightenment: The Debate over “Maladies Des Femmes” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993).

[2] Lisa Forman Cody, Birthing the Nation: Sex, Science and the Conception of Eighteenth-Century Britons (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[3] Londa Schiebinger, The Mind Has No Sex? (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989); Carolyn Merchant, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1980).

[4] The discourse concerning ignorant country midwives is part of a larger discourse concerning peasants and health. Within medical discourse of the eighteenth century generally and that of the Société Royale de Médecine (SRM) in particular, physicians cast the peasant as eternally childlike, ruled by their emotions and superstition. The SRM saw the supposed irrationality, emotionality, and religiosity of the peasant as obstacles to overcome if they wished to promote health in the countryside. Harvey Mitchell, “Rationality and Control in French Eighteenth-Century Medical Views of the Peasantry,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 21, no. 1 (1979).

[5] Schiebinger, The Mind Has No Sex?

[6] Joan Scott, The Fantasy of Feminist History (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

[7] Ibid., 5.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Renato Mazzolini, “Plastic Anatomies and Artifical Dissections,” in Models: The Third Dimension of Science, ed. Nick Hopwood Soraya de Chadarevian (Stanford University Press: Stanford, 2004); Rebecca Messbarger, The Lady Anatomist (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010).

[10] Anonymous, “Lettre D’un Citoyen, Amateur Du Bine Public, À M***, Pour Servir De Défense À La Mission De La Dame Du Coudray,” (Paris: P.G. Simon, 1777).

[11] André Levret, L’art Des Accouchemens, Démontré Par Des Principes De Physique Et De Méchanique, 3rd ed. (Paris: Chez p Fr Didot le jeune, 1766); Observations Sur Les Causes Et Les Accidents De Plusieurs Accouchemens Laborieux, 2nd ed. (Paris: Delaguette, 1750).

[12] Nina Rattner Gelbart, The King’s Midwife (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 61; Arlette Dubois, “La Machine De Madame Du Coudray-1778,” in La “Machine” De Madame Du Coudray Ou L’art Des Accouchements Au Xviiie Siècle, ed. Musée Flaubert et d’histoire de la Médecine- Rouen (Bonsecours: Point de Vues, 2004).

[13] “La Machine De Madame Du Coudray-1778.”; ibid.

[14] Gelbart, The King’s Midwife, 61.

[15] Dubois, “La Machine De Madame Du Coudray-1778.”

[16] Le Bas, Précis De Doctrine Sur L’art D’accoucher (Paris: Prevost, 1780), 11-12.author’s translation

[17] Anonymous, “Lettre D’un Citoyen, Amateur Du Bine Public, À M***, Pour Servir De Défense À La Mission De La Dame Du Coudray,” 2.

[18] Mouton, “Lettre Écrite De Sainte Menehoud, Le 29 Février 1776 Par M. Mouton, Procureur Au Bail[Sic]Age Et Subdélégué,” Gazette de Santé, April 18 1776, 67.

Bibliography

Anonymous. “Lettre D’un Citoyen, Amateur Du Bine Public, À M***, Pour Servir De Défense À La Mission De La Dame Du Coudray.” Paris: P.G. Simon, 1777.

Bas, Le. Précis De Doctrine Sur L’art D’accoucher. Paris: Prevost, 1780.

Cody, Lisa Forman. Birthing the Nation: Sex, Science and the Conception of Eighteenth-Century Britons. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Dubois, Arlette. “La Machine De Madame Du Coudray-1778.” In La “Machine” De Madame Du Coudray Ou L’art Des Accouchements Au Xviiie Siècle, edited by Musée Flaubert et d’histoire de la Médecine- Rouen. Bonsecours: Point de Vues, 2004.

Gelbart, Nina Rattner. The King’s Midwife. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Levret, André. L’art Des Accouchemens, Démontré Par Des Principes De Physique Et De Méchanique. 3rd ed. Paris: Chez p Fr Didot le jeune, 1766.

———. Observations Sur Les Causes Et Les Accidents De Plusieurs Accouchemens Laborieux. 2nd ed. Paris: Delaguette, 1750.

Mazzolini, Renato. “Plastic Anatomies and Artifical Dissections.” In Models: The Third Dimension of Science, edited by Nick Hopwood Soraya de Chadarevian. Stanford University Press: Stanford, 2004.

Merchant, Carolyn. The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution. San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1980.

Messbarger, Rebecca. The Lady Anatomist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Mitchell, Harvey. “Rationality and Control in French Eighteenth-Century Medical Views of the Peasantry.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 21, no. 1 (1979): 82-112.

Mouton. “Lettre Écrite De Sainte Menehoud, Le 29 Février 1776 Par M. Mouton, Procureur Au Bail[Sic]Age Et Subdélégué.” Gazette de Santé, April 18 1776.

Schiebinger, Londa. The Mind Has No Sex? Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989.

Scott, Joan. The Fantasy of Feminist History. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011.

Wilson, Lindsay. Women and Medicine in the French Enlightenment: The Debate over “Maladies Des Femmes”. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.