Spiritual Utopias: Researching Early Women’s Convents

by Alexandra Verini

Considering the difficulties of constructing a history of medieval women, Jo Ann McNamara has asked, “Can we write a history for which there were no historians, from records that resist the project?”[1] This seemingly impossible task is a common hurtle for feminist scholars of early periods, as the records of women’s lives are often scattered and piecemeal. My research on medieval and early modern women’s religious communities, for which I traveled to England and Germany last fall, has often run up against the uncertainties and absences of the historical record. More than their male counterparts, female monasteries suffered from a lack of resources and the destruction of their records, factors that make studying them challenging. At the same time, the very frustrations involved in putting together the pieces of these records have given me insight into these women’s lives. The fragmentary and accidental nature of their archives, both what survives and what does not, has helped me see how the limitations imposed on early religious women allowed them to develop alternative and often radical models of self and community.

My study of medieval and early modern religious women is part of my larger dissertation project, in which I examine women’s visions of ideal worlds produced or read in Anglophone contexts between the fifteenth and mid-seventeenth centuries. Though utopian writing existed from the classical age in works like Plato’s Republic, the word itself was coined by Thomas More, deriving from the Greek ou (no) and topas (place) but also punning on eutopas (a good place). Utopia then means “a good place that is nowhere.” After More wrote his book (Utopia) in 1516, this genre took off as a means for early modern Europeans to give narrative structure to the new geographic explorations that were taking place. Women in this time period were excluded from such voyages, as well as from male literary discourse, but they nonetheless produced their own visions of ideal worlds, which both drew on and differed from those of their male contemporaries. My project looks specifically at how women adapted utopian discourse, seeking to understand how they used this genre to develop models of same-sex friendship and community.

Early women’s utopic expression exists not only in fictional accounts of fantasy worlds but also in religious communities, which where focused on achieving a communal ideal and thus in creating a kind of spiritual utopia. To understand the workings of such real-world aspirational communities, I had to look at the records of convents. Because many of these records are unpublished and, in some cases, uncatalogued, I traveled to four research libraries in England and to a convent in Germany to view manuscripts, printed books and paintings in person.

Trading sunny skies for cool, rainy days, I arrived in London in September. My main task was to view the records of Syon Abbey, a convent from the order founded by St Bridget of Sweden, of which a branch was established in England in 1415. This order, which is the focus of my second chapter, was unusual in that it consisted of both nuns and monks, co-ruled by an abbess and a priest. It eventually became one of the wealthiest and more respected abbeys in England, publishing many of its in-house religious treatises for a wider, lay audience. After the Reformation, when England became Protestant and the monasteries were dissolved, the Syon community suffered considerable hardship, fleeing to Europe, first to France and eventually settling in Lisbon, where they stayed for two and a half centuries.

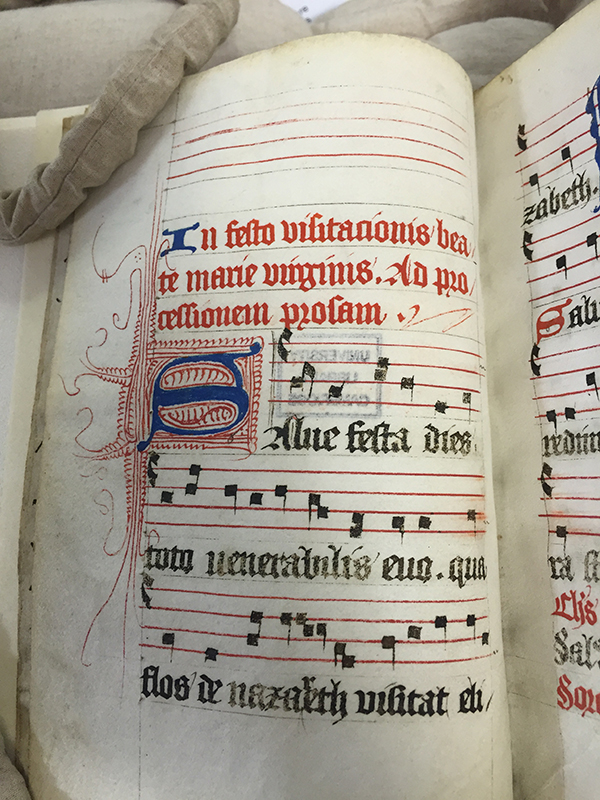

The manuscripts that survive from the abbey’s medieval period are dispersed across libraries, and nothing survives by nuns themselves before the seventeenth century. I therefore had to work with what McNamara characterizes as gaps and silences in the archive, looking at texts produced for the Syon nuns and imagining how these women might have read them and used them to construct their own visions of spiritual community. For these purposes, liturgical texts, which contain instructions for religious ceremonies, were particularly useful. At Oxford and Cambridge Universities, I viewed and transcribed several of these decorative texts, which contain prayers accompanied by musical scores (see figure 1), looking for passages that directed the sisters to move in certain ways or perform certain tasks. These explorations helped me see how even as these texts were written by male clerics to regulate the Syon nuns, by directing the sisters to process and chant together, they created the circumstances for female community.

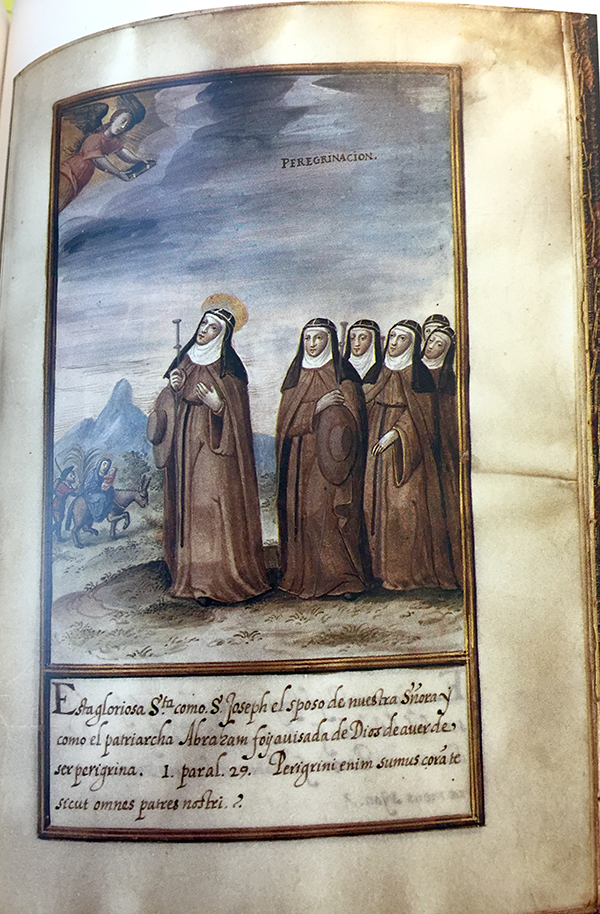

I later saw a different dimension of the community when I visited Arundel Castle and Exeter University, since these smaller archives contain manuscripts written or commissioned by the sisters after Syon Abbey had moved to Lisbon. Walking up the hill to Arundel Castle on a particularly rainy day, I felt like I’d stepped back in time, even more so when I mounted several sets of spiral stairs to a small and cluttered library to view a three-hundred-year–old illuminated manuscript. This book was produced by the sisters when they were living in Lisbon and was designed to persuade the king of Spain to help them return to England. To emphasize the community’s historical importance, it includes images of Syon’s history, beginning with Saint Bridget of Sweden receiving the Rule for her order from an angel (see figure 2). Turning the pages of this striking book, I gained a more visceral understanding of the incredibly high stakes of this endeavor and the turmoil in which the sisters were embroiled at that time.

My final stop in England was perhaps the most productive. When the few remaining English Bridgettine nuns returned to England in 1809, they settled in Devon, and, in 1990, they left their library in the care of Exeter University, where, with the help of kind and attentive librarians, I spent a week pouring over boxes of records. These included religious texts written for the nuns but also letters written by them, their vows of profession, and several intriguing and unpublished manuscripts written in the voices of the nuns. My visit to these archives gave me insight into the incredibly wide range of texts that these women would have encountered and produced, showing me how the diverse and scattered quality of this textual witness mirrors the circumstances of their lives. Just as the sisters often had to read against the grain of male-authored texts to produce their own visions of female spiritual community, I had to work with gaps, silences, and inconsistencies in the archive to understand the circumstances of their lives.

If Syon showed me how religious women could produce agency out of limitations, the second part of my travels helped me see the importance of looking across time and incorporating the present with the past in the study of women’s religious communities. After leaving England, I traveled to Augsburg, Germany, to visit the Congretatio Jesu, which is the focus of my third chapter. This community fwas ounded by Mary Ward (1585-1645), a recusant English Catholic who left England to found an institute that established schools for girls. At the Congretatio Jesu, one of several sites she founded that is still in operation, there are fifty painting of her life, showing her first as a young girl in England and eventually as an important religious figure, who strove to create an ideal female spiritual society.

On my trip to Augsburg, I had the opportunity not only to view these paintings in person (see figure 3) but also to meet with the present-day sisters. Arriving after several wrong turns, I had to communicate in broken German to explain that I was a graduate student writing my dissertation (partly) about Mary Ward. The sisters at the door seemed both excited and confused but cheerfully found an England-speaking nun who showed me to the room with the paintings.

There were many things I didn’t know about the paintings: Who were the other women sitting with Mary Ward in #22? Who were the figures in the background in #36? Since I hadn’t been able to find answers to these questions in my research, I didn’t expect the sisters to know either. Surprisingly, however, Sister Gertrude, one of the few English speakers, was able to answer almost all of my questions. It seemed that information about the paintings that had never been recorded in books had been passed down by word of mouth among the sisters of the Institute. At the end of my visit with the paintings, they invited me for a simple lunch of soup and spaghetti, during which I spoke more to them about what it was like to follow in the footsteps of Mary Ward and what had happened to the community in recent years.

This visit, so different from my solitary days with the archives in England, reminded me about the temporal dimensions of utopias, which, after all, interweave past, present and future, imagining new worlds that inevitably respond to, critique, and build on past ones in ways that serve as models and warnings for the present. The women at the convent in the twenty-first century were leading their lives according to mandates set down in the seventeenth century, following the examples of women of the past to set a model for the future.

When I looked more closely, I found this transtemporal focus in many of the women’s utopias that I was studying. Because there were so few examples of women with authority, female writers and spiritual leaders had to look to examples from the past, from the classical age and the Bible, and to create templates that they then projected into the future. More than religious men, whose agency was readily accepted and for whom there were many precedents, women in religious communities had to live on the threshold between what was and what could be, creating space for their authority in between times. By helping me to understand these new dimensions of women’s utopia, my research trip this fall, with the combination of the scattered archives of Syon Abbey in England and living nuns at Mary Ward’s Institute in Augsburg, offered vital information about women’s utopian communities in more ways than I expected.

Alexandra Verini is a Ph.D candidate in the Departmentof English at UCLA with a focus on medieval and early modern literature. She is currently working on her dissertation, “’A New Kingdom of Femininity:’ Medieval and Early Modern Female Alliance and Utopia.” She received a CSW Travel Grant to fund her research in the fall of 2015.

[1] Jo Ann McNamara, “De quibusdam mulieribus: Reading Women’s History from Hostile Sources,” Medieval Women and the Sources of Medieval History, ed. Joel T. Rosenthal (Athens, GA, 1990), 239.

Comments are closed.