Music and India’s Hijra Community

by Jeff Roy

The hijras (Third Gender communities) of India were historically embraced for their roles as musical purveyors of heteroconjugality (see Waugh 2001:127). Spiritually valorized yet socially marginalized, hijras can be spotted today in performances ranging from badhais––musical blessings for the birth of a newborn baby, marriage, or store opening––to risqué bar dance in urban Mumbai. But, being hijra is––and always has been––more than just about community service to normative society. While recognizing the utility of performance to the hijra way of life, my research centers on the ways music affirms and engenders notions of self-understanding for the hijras that do the musicking.

While conducting fieldwork in Mumbai during periods between 2010-2015, I found that calling oneself hijra is not simply an act of identifying as Third Gender, or transgender as many now declare, but also signifying one’s belonging to a gharānā. The word gharānā is employed in Hindustani (North Indian) music culture to refer to a “family tradition” or a “stylistic school and/or members of that school” (Neuman 1990:272). It is both a system of musical instruction and a familial way of life that binds a community of gurus and their disciples together. Unlike Hindustani gharānās in the past, however, belonging to a hijra gharānā is determined neither by pedigree nor by prescribed physical attributes, but upon a desire––or as some in the community have called an “inherent gift”––to embody new praxes of self-understanding based on reconstituted parameters of gendered identity. The bond between a chela (disciple) and her guru is important to this process, and because of this, frequently commemorated at exclusive celebrations and ceremonies known as jalsas (meetings, or celebrations).

In the summer of 2010, I was invited to attend and document a jalsa that took place on the grounds of an upscale hotel in a relatively remote area on the outskirts of Mumbai. It was an overnight affair celebrating the literal “comings out” of a chela named Sowmya in front of her guru Nita, the gharānā, and a community of over 75 hijras and close friends. The event concluded a 40 day period of Sowmya’s complete isolation following the symbolic, rather than actual, act of castration. In this picture, you can see a meeting that took place between the veiled Sowmya, her guru Nita, and myself about two weeks before the jalsa was scheduled to take place. (See figure 1.)

Arnold van Gennep might have called Sowmya’s jalsa her “rite of passage” into the hijra community. Acoustic music was played, recorded Bollywood music was danced, and a number of wedding-style rituals took place, including tel baan (putting turmeric paste on the chela), mangalaya dharanam (wearing auspicious jewelry), gift giving, a procession, and final vow. But, Sowmya’s “passage” was more than simply a performative “rite” (like saying ‘I do’). It was also a drawn out, highly visceral, and somewhat chaotic affair involving a great deal of vigorous music-making and dancing.

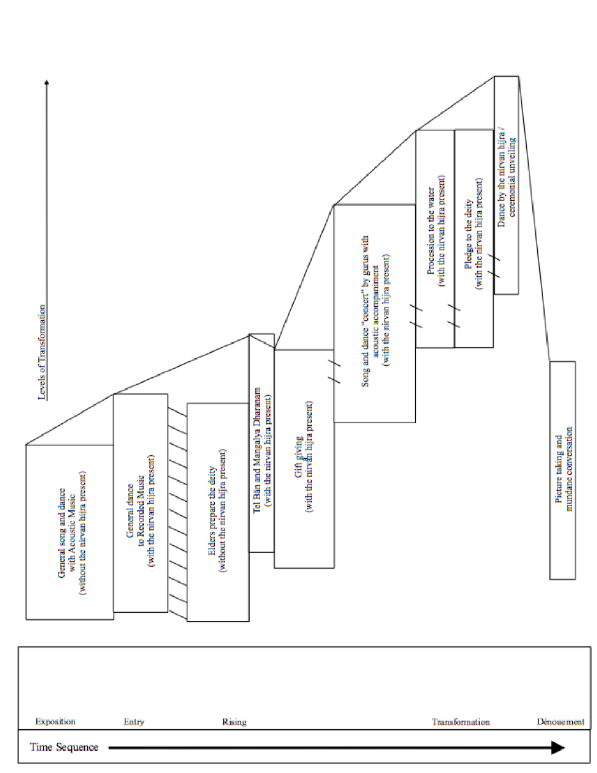

In my presentation, I showed how the progression of music and dance played an important part in Sowmya’s sensorial experience of becoming a chela. To explain this, I turned to A.J. Racy’s description of tarab (ecstasy) performance in the Near East jalsah (informal gathering). Often taking place around the time of wedding, tarab is not just a jam session between musicians, but a carefully orchestrated–yet–improvised series of musical phases that are gradually unfolded, linked within the larger structure of the jalsah, and ordered in a way that contributes to the jalsah’s emotionally transformative purpose (Racy 2004:53). Much like the Near East jalsah, sessions of improvised music-making and dancing at the hijra jalsa were performed in a way that induced feelings of ecstasy, or what is called mukhti in Hindi. The following diagram is a visual rendition of Racy’s tarab model (2004:57) depicting the sequential flow of the stages of emotional transformation over the axis of time at the hijra salsa. (see figure 2.)

Throughout most of the jalsa, Sowmya was segregated from the general community, and only her immediate family members were invited to witness the wedding-style rituals. Then, following the procession and final vow, Sowmya was encouraged to conclude the evening with a solo dance of her own. In my paper, this is where my understanding of the jalsa departed slightly from the tarab model. For Sowmya and her community, this “formal unveiling” was more than just about achieving emotional ecstasy for ecstasy’s sake. The music and dance were meant to do something more.

Within the hijra community, those who undergo this process are said to become nirvan––liberated. But, it is also said that with “liberation” comes a real responsibility to maintain and uphold the stated tenets of becoming hijra. As I showed, music and dance helped to fasten the bond between that feeling of transformation and the social realities that present themselves when entering a new phase of life. Mukhti created the space, movement, and artistic capacity for the emancipation, sanctification, and reconfiguration of Sowmya’s self-understanding as hijra within the reconstituted parameters of the guru-chela relationship. (See figure 3.)

Figure 3: Sowmya dances in formal unveiling. Still from video footage captured by the author, September 20, 2010

As Dwight Conquergood explained once during a graduate seminar course, “sometimes […] you do have to go there to know there” (in McCune 2008:6). For the presentation, I wanted my viewers to understand as accurately as possible Sowmya’s (and my own) positionality in the architectural space of the jalsa. So, I played a video of (almost) raw footage of the jalsa and asked that viewers contemplate not only the merits of my analysis––which was revealed in the video’s subtitles––but also the emotional affect of the sound and imagery. Like observational and vérité style documentary, the footage was edited to communicate a sense of duration as it was experienced in real time. (See film: https://vimeo.com/141306241 [password: pehchaan])

What is the use of all of this?

Through this research, I am looking to accomplish a number of things. First, I hope to contribute to the growing body of literature and films that provide an “emic” perspective of hijra culture. At its best, this work will help to counter the overwhelming material that gaze upon hijras through essentialist lenses. Second, I hope to provide a look at some of the ways that hijra identity corresponds to and departs from globally-endorsed ideas about transgender. This is a topic that I tackle in greater detail in an upcoming article for Transgender Studies Quarterly. And finally, I hope to contribute to a growing body of artistic works and literatures on India’s LGBT liberation movement, while maintaining a critical eye on the ways it intersects with the global gender and sexual liberation movement.

In many ways, my SEM presentation owes its existence to my dissertation, which despite possessing a chapter on the jalsa, took a decidedly introspective route. My dissertation investigates how my queer American frame(s) of reference and ethnographic methodologies are tied to the creation of the field. Engaging issues of representation, I argue that my documentation of hijra performance participates in and alongside identity-forming practices––something that can be called pehchān (acknowledgement, recognition, or identity)––by reconstituting preexisting tropes of the devalorized hijra through a lens of transgender respectability and professionalism. Of course, this is not something that filmmaking does exclusively on its own, but also in accordance with the community’s interest in producing self-representations of respectability that align with contemporary messages of affirmation in India’s LGBTIQ liberation movement. I will be expanding on some of these thoughts in a future essay for the upcoming anthology Queering the Field: Sounding Out Ethnomusicology: http://www.queeringthefield.com/.

My paper also owes its existence to the success of my course “Ethnomusicology of the Closet,” which was selected last year for the Collegium of University Teaching Fellows program and renewed for a second term in the Department of Ethnomusicology for the Spring Quarter. This course was created not only stimulate long-awaited ethnomusicological discourse on issues of gender and sexuality, but also to promote opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration between faculty and students across campus. We tackled such questions as: What can music tell us about a nation, (sub-)culture, or musician’s understandings about and relationships to gender and sexuality? What are the different ways culture-bearers participate in the packaging, endorsing, dispelling, and/or propagating of gender and sexuality? How do representations of gender shift across cultural borders in rhythm with social contexts, social movements and cultural practices, and how do they cross-pollinate through the mediascape? What kind of social impact do these performances achieve, if any? A weekly lecture-demonstration series with UCLA scholars, musicians, and other culture bearers helped us explore possible answers to these and other questions. Students also contributed to the richness of the course material themselves by presenting on a topic of their own choosing and incorporate what they learned into the development of a final ethnographic research project.

This year, I’ll be embarking on another intellectual journey with a new group of bright undergraduate students, and welcoming the return of a number of artists who graciously volunteered their time to speak in class. These include professional Vogue dancer Kevin Stea, Avenue Q creator Jeff Marx, and transgender dancer and actress Maya Jafer. Come join us for more exciting discussions! For a description of the original concept of course, visit this digital article on the Ethnomusicology Review Sounding Board: http://ethnomusicologyreview.ucla.edu/content/ethnomusicology-closet-new-undergraduate-course-offered-ucla.

Jeff Roy recently received his Ph.D. and currently serves as a Lecturer in the Department of Ethnomusicology at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). His research focuses on transgender and hijra performance through the lens of documentary filmmaking, and has been supported from fellowships by Fulbright-mtvU, Fulbright-Hays, the American Institute for Indian Studies, the Society for Asian Music, and UCLA.

Author’s note: In December 2015, I presented a paper at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Ethnomusicology (SEM) in Austin, Texas. Thanks to the support of a CSW Travel Grant, this was the fifth SEM conference in which I was able to participate. With this blog post, I plan to summarize the paper and provide a window into some of the other gender research that I have been doing as a graduate student in the Department of Ethnomusicology.

Works Cited

Gennep, Arnold Van. 1960. The Rites of Passage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McCune, Jeffrey Q. 2008. “‘Out’ in the Club: The Down Low, Hip-Hop, and the Architecture of Black Masculinity,” Text and Performance Quarterly 28: 3, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10462930802107415

Neuman, Daniel M. 1990. The Life of Music in North India. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Racy, Ali Jihad. 2004. Making Music in the Arab World: The Culture and Artistry of Tarab. New Work: Cambridge University Press.

Waugh, Thomas. 2001. “Queer Bollywood, or I’m the Player You’re the Naive One: Patterns of Sexual Subversion in Recent Indian Popular Cinema.” In Keyframes: Popular Cinema and Cultural Studies, edited by Matthew Tinkcom and Amy Villarejo. London: Routledge, 280:297.

Comments are closed.