Hello Kitty Love/Hate: On Asian Cuteness, Disability, and Affect

by Sharon Tran

My Hello Kitty Story

My first tangible memory of Sanrio’s anthropomorphic white cat is rather unremarkable. I remember spying a small plush Hello Kitty in a shop in New York’s Chinatown that I simply had to have. I remember pleading with my parents until they finally broke down and how I played with her and took her everywhere with me for a whole month—a lifetime in the attention span of a child. My second tangible memory of Hello Kitty is one that I still struggle to untangle and make sense of even now. In elementary school when class still began with a “Do-Now,” I remember finishing the assignment before my fellow peers and pulling out a book to read quietly. The teacher must have been impressed because she exclaimed, “Look at Sharon, everyone. Now that is a Hello Kitty star pupil.” I remember a moment of stunned surprise from being conflated with my beloved Sanrio character. What inspired my teacher’s pop cultural metaphor and how am I like my plush doll friend? What qualities allow Hello Kitty (and I) to exemplify a “star pupil”? Was my teacher praising my performance of Hello Kitty’s mouthlessness by reading quietly to myself? This Hello Kitty memory, its messy entanglement in classroom disciplinary politics and histories of gendered Asiatic racialization, has inspired my own scholarly interest in Hello Kitty and the kawaii (“cute”) political aesthetics she embodies. Building on the work of scholars such as Christine Yano, Anne Allison, and Sharon Kinsella, my research probes the serious critical stakes of kawaii for thinking Asian/American feminism.[1]

My first tangible memory of Sanrio’s anthropomorphic white cat is rather unremarkable. I remember spying a small plush Hello Kitty in a shop in New York’s Chinatown that I simply had to have. I remember pleading with my parents until they finally broke down and how I played with her and took her everywhere with me for a whole month—a lifetime in the attention span of a child. My second tangible memory of Hello Kitty is one that I still struggle to untangle and make sense of even now. In elementary school when class still began with a “Do-Now,” I remember finishing the assignment before my fellow peers and pulling out a book to read quietly. The teacher must have been impressed because she exclaimed, “Look at Sharon, everyone. Now that is a Hello Kitty star pupil.” I remember a moment of stunned surprise from being conflated with my beloved Sanrio character. What inspired my teacher’s pop cultural metaphor and how am I like my plush doll friend? What qualities allow Hello Kitty (and I) to exemplify a “star pupil”? Was my teacher praising my performance of Hello Kitty’s mouthlessness by reading quietly to myself? This Hello Kitty memory, its messy entanglement in classroom disciplinary politics and histories of gendered Asiatic racialization, has inspired my own scholarly interest in Hello Kitty and the kawaii (“cute”) political aesthetics she embodies. Building on the work of scholars such as Christine Yano, Anne Allison, and Sharon Kinsella, my research probes the serious critical stakes of kawaii for thinking Asian/American feminism.[1]

Hello Kitty’s Kawaii Political Aesthetics

Designed by Shimizu Yūko, Hello Kitty was first introduced in Japan in 1974 and marketed in the U.S. in 1976.[2] By 2014, Hello Kitty has evolved into a global marketing phenomenon worth approximately $7 billion dollars a year.[3] From her kitten softness and smallness to her round, simple contours, Hello Kitty embodies all the formal properties of kawaii. Connoting a sense of vulnerability, passivity, and pitifulness, kawaii is also defined in terms of the affective response it elicits: tender maternal feelings to hug, cuddle, and care for. The kawaii political aesthetics that Hello Kitty exemplifies sits uncomfortably with Asian American studies for a number of reasons.

As an aesthetic embedded in structures of global racial capitalism, kawaii can only seem to promise a compromised form of soft power. In his 2002 article, Douglas McGray contends that while Japan’s status as a military-economic power has diminished since its unconditional defeat during WWII and the asset-price bubble collapse in the early 1990s, the nation has accumulated a wealth of soft power by capitalizing on its cultural industries.[4] Unlike “hard power,” which relies on force, coercion, and payment, “soft power,” according to Joseph Nye, operates via attraction and cooptation.[5] As an aesthetic that seemingly invites its own consumption, kawaii can be viewed as an exemplary form through which Japan can claim and exert soft power. The power and success of kawaii goods, however, hinges, on what Koichi Iwabuchi terms, cultural deodorization: the self-conscious attempt to evacuate any overt, negative markers of racial otherness/foreignness from cultural products.[6] While Hello Kitty exudes some foreign Oriental appeal she simultaneously feels familiar, safe, and nonthreatening,[7] as an adorable anthropomorphic white cat.[8] Kawaii’s soft power, which is heavily structured and circumscribed by global racial capitalism, thus raises questions of kawaii’s critical potential and usefulness for Asian American studies. Soft power indeed seems untenable for a field founded upon Yellow Power, the militant affects and political activism that fueled the 1960s Civil Rights Movement.

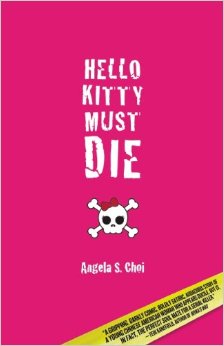

Asian Americanists have precisely renounced Hello Kitty because of her softness and soft power, how she promotes commodity fetishism and the racial-cultural stereotyping of Asia and Asian/American women by way of kawaii.[9] For Angela Choi, Denise Uyehara, and other Asian American artist-activists, Hello Kitty embodies the sweet, docile, and passive Asian female stereotype that must be vehemently contested.[10] In her novel, Hello Kitty Must Die (2010), Angela Choi writes: “I hate Hello Kitty. I hate her for not having a mouth or fangs like a proper kitty. She can’t eat, bite off a nipple or finger, give head, tell anyone to go and fuck his mother or lick herself. She has no eyebrows, so she can’t look angry. She can’t even scratch your eyes out. Just clawless, fangless, voiceless, with that placid, blank expression topped by a pink ribbon.”[11] Choi calls attention to how Hello Kitty’s cuteness relies on the violent aestheticization of disability. Hello Kitty is kawaii because she cannot speak, eat, bite or do anything. In her pivotal article, Sianne Ngai emphasizes how the “exaggerated passivity and vulnerability” of the cute object can provoke ugly, aggressive feelings in addition to the expected tender, maternal ones.[12] Choi’s call for the death of Hello Kitty adheres to the historical affective orientation of Asian American studies: righteous anger against racism and gendered Orientalist stereotypes. Yet I am interested in how this Asian Americanist hatred of Hello Kitty also has to do with the field’s deep investment in a Marxist, leftist politics that celebrates a productive, resistant, and fully able/autonomous Asian American body.

Asian Americanists have precisely renounced Hello Kitty because of her softness and soft power, how she promotes commodity fetishism and the racial-cultural stereotyping of Asia and Asian/American women by way of kawaii.[9] For Angela Choi, Denise Uyehara, and other Asian American artist-activists, Hello Kitty embodies the sweet, docile, and passive Asian female stereotype that must be vehemently contested.[10] In her novel, Hello Kitty Must Die (2010), Angela Choi writes: “I hate Hello Kitty. I hate her for not having a mouth or fangs like a proper kitty. She can’t eat, bite off a nipple or finger, give head, tell anyone to go and fuck his mother or lick herself. She has no eyebrows, so she can’t look angry. She can’t even scratch your eyes out. Just clawless, fangless, voiceless, with that placid, blank expression topped by a pink ribbon.”[11] Choi calls attention to how Hello Kitty’s cuteness relies on the violent aestheticization of disability. Hello Kitty is kawaii because she cannot speak, eat, bite or do anything. In her pivotal article, Sianne Ngai emphasizes how the “exaggerated passivity and vulnerability” of the cute object can provoke ugly, aggressive feelings in addition to the expected tender, maternal ones.[12] Choi’s call for the death of Hello Kitty adheres to the historical affective orientation of Asian American studies: righteous anger against racism and gendered Orientalist stereotypes. Yet I am interested in how this Asian Americanist hatred of Hello Kitty also has to do with the field’s deep investment in a Marxist, leftist politics that celebrates a productive, resistant, and fully able/autonomous Asian American body.

Towards an Alternative Affective Politics

The contention surrounding Hello Kitty’s mouthlessness renders salient how one effect of the mass commodification of vulnerability via kawaii is to breed Marxist contempt for the vulnerable. Sanrio’s official response to why Hello Kitty does not have a mouth is so that she can serve: “as a sounding board to synchronize with the mood of the viewer.”[13] The openness of Hello Kitty’s kawaii form, which facilitates and depends on affective connection, draws her and the viewer into intimate sociality. In taking seriously Sanrio’s explanation and the soft power of kawaii, I am not literally endorsing cute consumerism as a feminist tool but rather calling attention to how Hello Kitty’s kawaii aesthetics allow us to imagine an alternative to a Western leftist politics grounded in liberal ideologies of autonomous individualism. Drawing on disability studies, I argue that Hello Kitty’s mouthlessness, which serves as a symbol of racial injury and entails a particular kind of wounded embodiment, can also illuminate an alternative affective approach to and way of doing politics that accentuates a “being-with” in vulnerability.[14] I probe how nonnormate, nonautonomous modes of embodiment can, in James Kyung-Jin Lee’s words, delineate and provide “the basis for a new pedagogy and politics of alternative social being.”[15]

In my larger dissertation project I elaborate on how the political aesthetics of kawaii contour a radically new feminist and disabled notion of social political collectivity through an analysis of popular Japanese anime series such as Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon (March 7, 1992–February 8, 1997)[16] and Puella Magi Madoka Magica (January 7, 2011–April 21, 2011).[17] I also examine the migration of kawaii aesthetics to other genres, in particular, Chang-rae Lee’s futuristic, speculative novel On Such a Full Sea (2014).[18]

Author’s note: I am extremely grateful to the Center for the Studies of Women at UCLA for awarding me a travel grant to present my research at the annual Pacific Ancient and Modern Languages Association in Portland, Oregon. I received very helpful and generous feedback from my fellow panelists as well as other conference attendees towards further developing my research on the so-called phenomenon of “Asian cuteness” in relation to disability studies and affect theory. Finally, I was really excited to contribute to new initiatives to build a stronger reputation and platform for Asian American literary studies, which has been historically underrepresented at PAMLA.

Sharon Tran is an English doctoral candidate at UCLA, specializing in Asian American literature and culture. Her research interests include critical race studies, gender and sexuality studies, affect theory, and visual culture. She is currently working on her dissertation titled, “Between Asian Girls: Minor Feminisms and Sideways Critique.” She is the 2016 recipient of the Penny Kanner Dissertation Research Fellowship.

Notes

[1] See: Christine Yano, Pink Globalization: Hello Kitty’s Trek across the Pacific (Durham: Duke UP, 2013); Anne Allison, Millennial Monsters (Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006); and Sharon Kinsella, “Cuties in Japan,” in Women, Media, and Consumption in Japan, eds. Lise Skov and Brian Moeran (New York: Routledge, (1995) 2013), 220-54.

[2] Yano, Pink Globalization, 9, 87.

[3] Jenee Osterheldt, “At 40, Hello Kitty is Timeless,” The Kansas City Star, June 23, 2014, accessed October 19, 2014, http://www.kansascity.com/living/liv-columns-blogs/jenee-osterheldt/article603120.html

[4] Douglas McGray, “Japan’s Gross National Cool,” Foreign Policy: The Magazine of Global Politics, Economics, and Ideas, May 1, 2002, accessed March 5, 2015, http://homes.chass.utoronto.ca/~ikalmar/illustex/japfpmcgray.htm.

[5] Joseph Nye, Soft Power (New York: PublicAffairs, 2004).

[6] Koichi Iwabuchi, Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism (Durham: Duke UP, 2002), 28.

[7] See Christine Yano’s discussion of the “foreign as familiar” appeal of Hello Kitty (Pink Globalization, 253-54).

[8] “Hello Kitty Profile,” SanrioTown, accessed October 19, 2015, http://hello-kitty.sanriotown.com/. Hello Kitty’s official character profile indicates that she is a British girl and serves as Sanrio’s attempt to cater to the 1970s Japanese craze for all things British.

[9] Yano, Pink Globalization, 167.

[10] Japanese American performance artist, Denise Uyehara, developed an anti-cute performance piece titled Hello (Sex) Kitty Mad Bitch on Wheels (2002). Ann Poochareon, Geraldine Chung, and Vivian Wenli Lin, an Asian American female activist group working out of NYU’s Tisch School of arts released a short DVD video titled Hello Kitty is Dead (2003) that similarly uses Hello Kitty as a touchstone for critiquing gendered, racialized, Orientalist stereotypes of Asian/American women. See: Yano, Pink Globalization, 170-71.

[11] Angela S. Choi, Hello Kitty Must Die (Madison, WI: Tyrus Books, 2010), 16-17.

[12] Sianne Ngai, “The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde,” Critical Inquiry, 31, no. 4 (2005): 816. Leslie Bow’s 2015 AAAS conference presentation, “Racist Cute: Kawaii, Kitsch, Spectatorships,” addresses a similar idea of the “split affect” of the “racist cute.”

[13] Yano, Pink Globalization, 67.

[14] On “being-with” see: José Esteban Muñoz, “ ‘Gimme GImme This… Gimme Gimme That’: Annihilation and Innovation in the Punk Rock Commons,” Social Text 31, no. 3 (2013): 95-110.

[15] James Kyung-Jin Lee, “Pathography/Illness Narratives,” n The Routledge Companion to Asian American and Pacific Islander Literature and Culture, ed. Rachel Lee (New York: Routledge, 2014), 458-59.

[16] Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon (美少女戦士セーラームーン), TV series, March 1992-February 1997, directed by Junichi Satō, Kunihiko Ikuhara, and Takuya Igarashi, written by Sukehiro Tomita, Yōji Enokido, and Ryōta Yamaguchi, produced by Toei Animation.

[17] Puella Magi Madoka Magica (魔法少女まどか☆マギカ), TV series, January 7, 2011-April 21, 2011, directed by Akiyuki Shinbo, written by Gen Urobuchi, produced by Shaft and Aniplex.

[18] Chang-rae Lee, On Such a Full Sea (New York: Riverhead Books, 2014).

Comments are closed.