Mysteries of the June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives: Martha Foster Collection

One of the joys of working in an archive, for archivists and researchers, is coming across tantalizing mysteries. A huge range of women have donated to The June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives, ranging from public figures like Margarethe Cammermeyer to lesser-known, but no less historically important, women. Occasionally, a very intriguing collection will come with a minimum of identifying information about the woman to whom it belonged. I interviewed Stacy E. Wood, a Graduate Student Researcher working on processing the Mazer collections for UCLA, about one such collection: The Martha Foster Collection.

One of the joys of working in an archive, for archivists and researchers, is coming across tantalizing mysteries. A huge range of women have donated to The June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives, ranging from public figures like Margarethe Cammermeyer to lesser-known, but no less historically important, women. Occasionally, a very intriguing collection will come with a minimum of identifying information about the woman to whom it belonged. I interviewed Stacy E. Wood, a Graduate Student Researcher working on processing the Mazer collections for UCLA, about one such collection: The Martha Foster Collection.

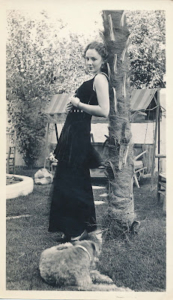

While looking through the Mazer holdings at UCLA, Wood came across Foster’s papers, which included a small amount of poetry and many striking photographs, taken in her backyard in Echo Park in the early 1930s. “They’re really gorgeous,” says Wood. “They almost look like test costume shots. There are hundreds of them. And I couldn’t find any information about her. Even Angela Brinskele (photographer and board member of the Mazer Archive) couldn’t find a death certificate or birth dates.”

Wood became fascinated with Foster, and went above and beyond the call of duty to find out more about her. She and Brinskele emailed friends and colleagues to try and unravel the mystery. Wood even went to Foster’s house to inquire about her.

“There was one letter with her old address on it,” says Wood. “So I went to her house and asked [about her], in case maybe her grandkids lived there. I felt really strange about my pilgrimage to her house, but I did it anyway! I went and knocked on their door, asked if they knew the previous owner, and said her name. They said no, and I took it at face value.”

Wood had given up on solving the mysteries of Martha Foster. However, six months later, strictly by coincidence, a new clue emerged.

“There is an accordion room divider at The Mazer‘s headquarters in West Hollywood, and it’s from the Esther Bentley collection. It is sort of a collage that she’s done. It’s called ‘The Women in My Life,’ and it’s rumored to be all of her ex-girlfriends. Peeking out, I saw Martha Foster’s face, and I freaked out, because this meant that she was sort of real and had real connections, and maybe I could find something about her.”

To her surprise, as Wood continued processing various Mazer collections, more fragments of information and memorabilia about Foster began to emerge.

“Looking through Esther Bentley’s collection, I found Martha’s ID card and some tax information about the house they shared in Echo Park,” says Wood. “And then these other bits of her life were in another person’s collection. Nobody at the Mazer knew that [any of these people] were connected.”

So far as Wood can tell, The June L. Mazer Lesbian Archive contains the only evidence of Foster’s life.

“Angela has been tracking down everything for the collection’s deeds, for legal purposes, and she even asked me to dig out Foster’s tax document because it says that she died, and we can’t find out through the city or online that she even existed. The only traces of her are in these collections, and some of them are in her ex-girlfriend’s collection. But we don’t know when they dated, or when they knew each other. There are just these sort of weird suggestions.”

Foster’s relationship with Esther Bentley makes the lack of information available about her even more confounding, as Bentley was a very well-known and well-connected member of the Los Angeles LGBTQ community.

“That’s the weird thing,” says Wood. “We know almost everything about her. Her collection is huge, everyone knew her. She was super active in L.A., everyone at the Mazer knew her. There are all sorts of stories about her. What’s strange is that the picture of Martha in the ex-girlfriend collage was taken when she was older, so I assume people would have known her or had some contact with her. But nobody knew her. She was with somebody who was very known in the community, but she herself doesn’t have any ties. The pictures are so beautiful. It’s like a silent film star posing in her backyard, in these beautiful, sort of Moroccan prints. You imagine who was taking those pictures, and you’ll never know. It drove me crazy for so long, for so many months.”

Before she began processing the Mazer archives, Wood anticipated that they’d contain more mysteries than they actually do. Her assumption seemed to be confirmed when the first collection she processed belonged to another very enigmatic subject named Tiger Woman. “Her poetry and some of her art work were in the collection, and again she dated someone who ended up being a famous and recognized artist,” says Wood. “I tried to contact the artist, and she would never respond to me. But it was a situation that was really frustrating, because I had all of these photos, and she felt more accessible because they were from the early 1990s. I couldn’t believe that someone would just drop off the planet, and that there was no trace of her.”

However, in spite of these archival mysteries, Wood has been surprised at how comprehensive the June L. Mazer Lesbian Archive is in its historicizing of lesbian identities. She believes that the archive can be so comprehensive because of its deep, strong roots in the community that it documents.

“Since Tiger Woman was the first collection I worked on, I expected it to be the norm: some of it due to mystery, and some of it due to a choice made by the subject of the collection,” says Wood. “A lot of people have collections that they gave at times in their life, and now they have different identities and politics. So I just expected it to be a little harder to pin things down in a traditional archival way. But [such challenges] haven’t happened as much as I would’ve thought, and I think that’s due to the organizational structure of the Mazer and the grassroots nature of it. If you can’t find something out, you activate the network, and it will come back to you. It might not come back soon, but in nine months somebody will send a facebook message to somebody else, and eventually it will come back to you: Here is what she is doing now.”

Wood admits that her own personal tendency to become passionately fascinated with the subjects of the collections she processes can sometimes drive her crazy. At the same time, it likely makes her perfect for the job. “I get very attached to the collections, and also sort of like to communicate some sort of story [from them]. There are false hopes attached to that desire. I think that especially with a project like this, when the idea is unearthing these lost, hidden, or less public histories, it seems even more important if you get almost obsessive about representing people in whatever way you can. So it’s almost more frustrating when you can’t put a picture together.”

Wood emphasizes that the more identifying information she can find about a collection, the more potentially useful it will be to a researcher. “Ultimately, it’s about people using this collection,” says Wood. “If you think about it that way, it’s important to have as much information as you can, so that people can know it’s there, and how they can use it. It’s hard to fit that sort of affective sense [that surrounds mysterious collections] into a finding aid. It’s hard to say: Oh, there are these beautiful pictures, and they’d be great for artists, designers, and period study, and there’s this poetry that’s not really great, but… It’s hard to say why a collection is important without giving it shape or context. It’s hard to piece it together.”

However, while there are abundant professional reasons for solving the mysteries of the archive, Wood has become an excellent detective because she loves the work. “I think I have some narrative greed, but that’s my own sort of personal problem,” says Wood. “I think it is in a lot of ways a hindrance to my actual job sometimes, because within the context of what we’re doing it’s actually not always practically important to know all of the information that I seek out. But it’s hard to work with these materials and not want to know.”

–Ben Raphael Sher

PS Do you know anything about Martha Foster or Tiger Woman? E-mail ben.sher.csw@gmail.com!

Ben Sher is a doctoral student in the Department of Cinema and Media Studies at UCLA and a graduate student researcher at CSW.

The finding aid for this collection will soon be available for viewing at the Online Archive of California(http://www.oac.cdlib.org). Digitized materials from the collection and the finding aid will be available for viewing on the UCLA Library’s Digital Collections website. This research is part of an ongoing CSW research project, “Making Invisible Histories Visible: Preserving the Legacy of Lesbian Feminist Activism and Writing in Los Angeles,” with Principal Investigators Kathleen McHugh, CSW DIrector and Professor in the Departments of English and Cinema and Media Studies at UCLA and Gary Strong, University Librarian at UCLA. Funded in part by an NEH grant, the project is a three-year project to arrange, describe, digitize, and make physically and electronically accessible two major clusters of June Mazer Lesbian Archive collections related to West Coast lesbian/feminist activism and writing since the 1930s.

For more information on this project, visit http://www.csw.ucla.edu/research/projects/making-invisible-histories-visible. For more information on the activities of the Mazer, visit http://www.mazerlesbianarchives.org